-

-

*A note to the reader:[edit]

-

This text has been written with the intention to be materialised in a very specific form; a set of A6-sized index cards, contained in a box. Please read it while holding the cards in your hands, shuffling and reordering them, making your own text as you read.

-

These cards list the tasks performed on the site of contingencies, the bootleg library. Tasks are described on the obverse, and related images and references are on the reverse.

-

-

Tasks of the Contingent Librarian[edit]

-

The library is closed, the shelves are empty, the librarian has gone. All that is left is a set of index cards contained in a box. At the top of each card is a verb introducing the tasks performed within the space and duration of a particular, situated social infrastructure called the “bootleg library”. The reverse includes references and images that illustrate each task.

-

This text was written with, by and for readers during library sessions. We wrote on cards by hand, we typed words in a collaborative writing environment. We wrote them together; humans and machines; texts were blended into a mix of keystrokes in changesets too complex, and dependencies too layered to determine singular authorship. These texts were never objects, always processes[1].

-

Participation from readers became a vital element in the practice of librarianship. The library grew, and we sustained it through conversation and correspondence. We wrote together in threads and strings; and so we created and maintained a space for publication. In the journey from private to public collection, texts were intermingled and rematerialised, gaining provenance and diversification through use. The readers are in the pages of the books, in the metadata of the library and on these cards, where traces of their presence remain.

-

This text will never be complete. It describes a particular, situated library, one that does not exist anymore, but resembles those that came before it and those that will succeed it. This set of cards is also a library, a collection organised into a structure that directs readers towards the interior, towards the texts it contains. This set is a book, a hyper-index, forever pointing outwards to other books, libraries, readers and writers. Text, library, book and index all come together in this particular material form to comprise a manual, a thing to be manipulated in the hands of readers.

-

Cards invite shuffling, re-organising, flipping over, distributing, annotating, laying out. An A6 card like the one you’re holding now fits comfortably into the palm of one’s hand, and can be easily turned as it is gripped between the index finger and thumb.

-

Cards have two sides. Arranged on a table, only one side is visible, and proximity determines connections. Held in the hands and flipped like a book, new relationships between the verso and recto pages emerge. The reader becomes the writer anew, determining what to keep or discard, what to edit or leave as is; the author of the sequence, connections and hierarchy between tasks.

-

-

-- ↑ Barthes, R., ‘From Work to Text’, in Barthes, R. and Heath, S. (1987) Image, music, text. London: Fontana Press.

-

-

-

acquiring/removing[edit]

-

see also administrating, finding texts, downloading

-

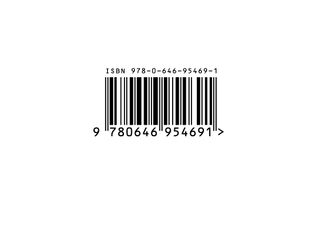

Many national libraries have acquisition programs in place with stringent, highly formalised procedures through which new texts enter the collection. Some countries require that an officially published book is donated to their national library by way of a system called “legal deposit”. Purchase of a commercial identifier such as an ISBN (International Standard Book Number) allows the book to be registered, so that other libraries that subsequently acquire the same text may share cataloguing details.

-

The library makes no such demands. Books are acquired through informal means, in ways that are not regulated or legislated. Anyone may remove or add texts to the library.

-

Image: ISBN barcode

-

-

finding texts[edit]

-

see also acquiring/removing, downloading, searching/browsing

-

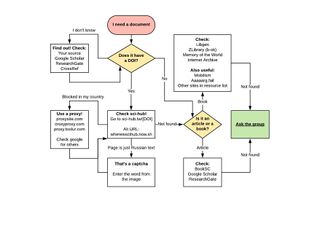

Most often, acquisition requests are as mundane as someone asking if the library has a particular text. A quick search online produces a digital file as a result. The provenance of these texts is buried in the file paths of the uploader’s computer, and the computers before it. Texts are acquired by any means necessary, through a social network, or through a digital network of so-called “shadow libraries” and groups of sympathetic readers. It’s often surprising how fast an unknown fellow reader will respond to a request for a text via certain groups operating on social media websites. Type F to follow this post.

-

Image: Flow chart from Facebook group Ask for PDFs from People with Institutional Access

-

-

uploading[edit]

-

see also acquiring/removing, amateuring, including/excluding

-

The digital collection is formed from individual uploads made by readers who care to share. Uploading takes time—a precious commodity for many readers—and each upload is a deliberate action, not an afterthought. Fostering a culture of uploading requires a decentralised network of readers, and likewise, librarians. A different notion of librarianship is required; the librarian is not the central hub of access to knowledge, but each reader should be a librarian, with the ability to produce, recommend and request texts from others.

-

Image: “When everyone is librarian, library is everywhere.” Quote from Why and How to Become an Amateur Librarian by Marcell Mars, Manar Zarroug and Tomislav Medak, available at https://www.memoryoftheworld.org/blog/2014/10/28/why_and_how_to_become_an_amateur_librarian/

-

-

downloading[edit]

-

see also acquiring/removing, finding texts, uploading

-

A reader who downloads and does not upload is a passive observer to the activities of the library. We prefer to be in the position of the downloader due to the legal penalties for uploading and redistributing copyrighted texts, which are far more severe than those for downloading. The library will not grow if all we do is take. A library is a collection of shared texts, and sharing is facilitated by both uploading and downloading.

-

Image: A download symbol

-

-

bootlegging[edit]

-

see also diversifying through use, multiplying form, republishing

-

Most people think of bootlegs as cheap knock-off products that masquerade as the real deal; bootleg cigarettes, designer-label clothes, not-quite-right imitations of Disney products and the like. Bootlegging began during the prohibition era with the practice of illegally distilling and distributing alcoholic beverages, often literally concealed in the leg of a boot while being transported. Run an image search on the keyword “bootleg” and you’ll probably see all sorts of suspicious-looking products. But the way I want to speak of bootlegging is as a social act, a homage, and one that creates and celebrates a multiplicity of form. I’m referring in particular to the vibrant culture of music sharing in the 1970s that followed portable cassette tape recorders entering the market. These allowed fans to cheaply record live performances and share these recordings—also known as bootlegs.

-

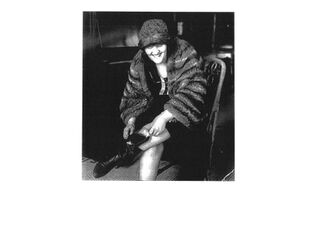

Image: A “bootlegger” concealing a flask of an illegally distributed alcoholic beverage in the leg of a boot during the Prohibition era

-

-

being kind to the reader[edit]

-

see also bootlegging, cleaning up text, diversifying through use, multiplying form, republishing

-

While bootlegging makes a fairly faithful reproduction of a source publication, the degree of transformation is sometimes due to unintentional or uncontrollable factors, such as availability of the equipment and materials needed to make a close copy. At other times, more deliberate choices can be made concerning the transformed materiality of the bootleg.

-

Economy, efficiency, and readability are the main concerns when bootlegging texts for the library. Economy often dictates that materials that are at hand are used—in the case of printed books for example, this often means defaulting to certain choices with paper, printing methods and binding. An efficient workflow is not too time-consuming. Although the most important thing is to have the text by any means necessary, we read best what we read most, and certain typographic concerns may become vital to the readability of the text.

-

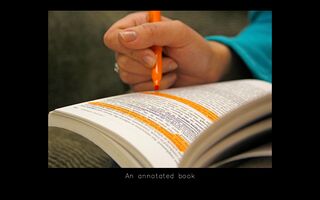

Being kind to the reader can involve adhering to typesetting conventions; including headers, footers and page numbers should the book be photocopied and pages subsequently separated from the others. Most importantly, a reasonable line length and wide margins will allow the book to be made in a way that ensures a comfortable reading experience and provides space for annotation.

-

Image: A bootleg copy of My Mother Was A Computer by N. Katherine Hayles. The source PDF has been reimposed into a booklet, with reasonable line length (60-80 characters) and ample space for annotations

-

-

diversifying through use[edit]

-

see also bootlegging, being kind to the reader, multiplying form, republishing

-

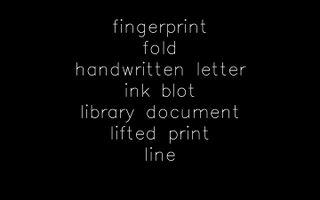

Publications acquire difference through reproduction; sometimes intentionally, always circumstantially. A printed book always ends up in the hands of at least one reader. It is transported, pages are dog-eared and annotated, time weathers the paper and cracks the spine. Multiply this by many readers, and each printed copy starts to accumulate its own traces, losing resemblance to the rest of the edition and acquiring its own particular countenance and provenance through use.

-

Image: 1. Books are for use.

-The first law of S. R. R. Rangathan’s 5 Laws of Library Science, 1931

-

-

multiplying form[edit]

-

see also bootlegging, diversifying through use, producing texts, republishing

-

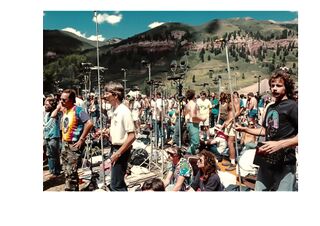

The jam band The Grateful Dead were followed around the United States by a legion of die-hard fans, proclaiming themselves “Deadheads”. Cheaply available cassette recorders allowed them to tape concerts and then share recordings amongst each other. Thinking of this, I’m reminded of John Cage’s motto, “Everything you do is music, and everywhere is the best seat.” Each position in the audience produces a slightly different recording, and this multiplicity of form connects the audience not only with the music, but with each other.

-

There are files in the library that are of the same text, but they have travelled different paths to get there, accumulating difference through methods such as annotation and material transformation. And so, they have different materialities, lending weight to the argument that a text is not identical with itself; that there is no such thing as a unique, singular, original “work”, but instead many different versions of texts, born through the accidents of their creation.

-

Image: “Deadheads” recording a live Grateful Dead concert, 1972

-

-

republishing[edit]

-

see also bootlegging, diversifying through use, multiplying form

-

Samizdat publishers considered a printed text to be officially published if it came in an edition of at least 5 copies. The library considers this to be excessive, and reduces that number to 1. One copy of a text can be shared and enriched by the accumulated annotations of many readers. A one-to-many-publishing model distributes texts to the widest possible public. The library instead insists on a many-to-one model, drawing many readers to one text. Republishing the one text many times creates a multiplicity of form, and subsequently a multiplicity of publics in each instance.

-

Image: Staff working at Publication Studio, London. Publication Studio is a federated publishing network with studios located worldwide. Books ordered from the shared catalog are printed and bound one-at-a-time by the closest studio. Differences in availability of paper and machinery at each studio means that the materiality of each instance of a printed text will vary depending on where and how the books are made.

-

-

cleaning up text[edit]

-

see also being kind to the reader, editing, typing

-

A text found in the wild often comes with visible and invisible artefacts. The visible ones come from bad OCR, with strange characters popping up in place of the ones you expect, such as a 1 instead of an l. The bane of the bootlegger is most definitely the line break or “soft return”, inserted by software that automatically breaks the line as you type. Screen-based formats such as EPUB don’t have the notion of a page, and flow text according to window size.

-

You can either be methodical and remove each soft return manually, or use the powerful automated find/replace all option. A useful tactic is to find every instance of a full stop followed by a space where a line was intentionally broken by the human writer. Next, replace each full stop with an arbitrary but uncommon character, such as a dagger (†). Then, do another find/replace and remove every instance of a soft return and a space, and finally replace the uncommon character with a full stop, in one final find/change command.

-Another unwanted character that often appears is the hyphen, inserted where words break at the end of a line. Here the pruning of errant characters is trickier, and the best method is to find each instance and remove them manually. Running find/replace all can often remove necessary hyphens, such as in time ranges (e.g. 9-5) and compound adjectives (e.g. inter-dependent).

-

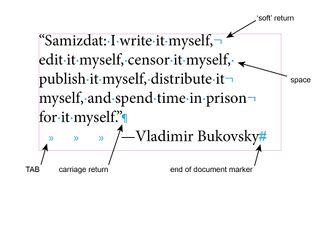

Image: Hidden characters (e.g. tabs, spaces, carriage and ‘soft’ returns)

-

-

editing[edit]

-

see also amateuring, multiplying form, republishing, rereferencing, typing, writing

-

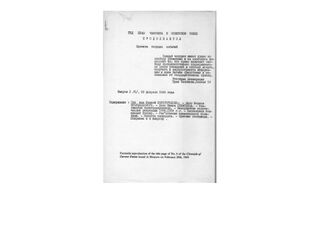

As soon as a reader edits a text its materiality changes either unintentionally, or through more intentional methods, such as republishing in a different format to make the text more accessible to a wider public. Samizdat publishers often considered themselves editors, or typists (rather than authors) due to the unwanted attention and risk that this credit would bring. As they reproduced texts by hand, a slippery form of authorship evolved through human error and also particular idiosyncratic preferences for a new phrase, approximate translation or text structure. Vladimir Bukovsky summarised the process of self-publishing as “Samizdat: I write it myself, edit it myself, censor it myself, publish it myself, distribute it myself, and spend time in prison for it myself.” The responsibility these self-proclaimed editors took upon themselves by republishing dissident material bound them to the texts; entwined in their creation and distribution. When no writer wants to be an author, everyone becomes an editor.

-

Image: Facsimile of A Chronicle of Current Events (Russian: Хро́ника теку́щих собы́тий), the longest-running Samizdat publication, (1968-1982)

-

-

repaginating[edit]

-

see also being kind to the reader, cleaning up text, editing, rebinding, reprinting, republishing, rereferencing

-

The simplest solution is to just print the source publication, but sometimes you might want to lay the text out again using a different format, font or layout, for reasons not worth going into in detail here. This means either the original text flow and page numbers should be the same, or there must be some references in the bootleg to the source publication.

-

Some observations and methods:

-

1) Justified text saves space and gives much more control over where to break the page.

-

2) The most basic reference system is to include an index that specifies which page in the source publication matches the bootleg. However, this is not so useful when setting text for a page (e.g. PDF), and more useful for EPUBs, which don’t have the notion of a page.

-

Inserting page numbers directly into the text can indicate where the page breaks in the source publication. This is quite time consuming, but it allows you a lot of freedom to differ between fonts, page and type size, text-block dimensions and page count.

-

Image: A page from a bootleg of Mladen Dolar’s A Voice and Nothing More, implementing new page numbers to mark the page breaks of the source publication

-

-

reprinting[edit]

-

see also being kind to the reader, bootlegging, rebinding, republishing

-

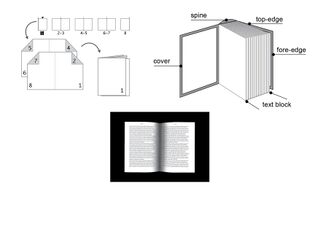

Making a printed book involves selection of paper stock and decisions on how to economise with the printing method. Often this calls for text to be imposed, 2-up, double-sided, into a booklet. Booklets are useful for thin, staple-bound books, less than 64 pages of ordinary 80gsm paper.

-

A text block of 2-up imposed spreads is cut in the middle first, then the two halves are joined together like a sandwich. Turning a single page document into a 2-up imposed PDF also imposes a constraint. There is no other way to create the text block. So, a book made in this way will result in a visible “split”, and the pages will naturally fall open where the two halves were joined.

-

This is because most commercially bought paper comes with the grain direction aligned with the long edge, not the short edge. The solution is to print pages, not spreads, 1-up, double sided on a page. If you can find a printer that takes sheets of paper smaller than A4 (such as A5) this is perfect, if not, you may have to concede the loss that comes from trimming down to a smaller than A5 size. Although this may seem just a superficial concern, the book will not be split, making for a materiality that emphasises the unity of the text.

-

Image: (clockwise from top left): imposition from a single-page PDF into a booklet, anatomy of a book, a spread

-

-

rereferencing[edit]

-

see also being kind to the reader, cleaning up text, editing, rebinding, repaginating, republishing, reprinting

-

Academic research requires citation, and inevitably this means referring to a quote from a book, located on a particular page. Citation allows readers to locate the reference efficiently. For this to happen, the reader must be able to find the text easily by searching for it in a catalogue system. Often books will include cataloguing information in the front matter, and for citation purposes this can be retained in a bootlegged book.

-

Digital files don’t always come with text that is suitable for print, particularly when the text is kerned too tightly or too loosely, or when bad OCR (Optical Character Recognition) returns characters that are not actually in the source publication. Sometimes a dark mark on a page will be interpreted as a character by OCR software. In these cases the text may need to be set again using a different format, font and page layout.

-

Image: A bootleg copy of The Open Work by Umberto Eco. Optical Character Recognition software has mistakenly rendered the page number (page 80) as the word “So”

-

-

rebinding[edit]

-

see also being kind to the reader, cleaning up text, editing, repaginating, republishing, reprinting, rereferencing

-

A perfect-bound book is typically made with cold glue (such as polyvinyl acetate), or glue that melts at high temperatures. The benefit of cold glue is that it allows the book to lie flat when opened, as the spine is flexible. Cold-glue bound books can be made by hand with quite rudimentary equipment. All you need is a printed text block and cover, a press, a piece of gauze or cheesecloth for the spine, and a brush to apply the glue to it. This takes a lot of time, practice, skill and patience to do by hand, but machines for cold-glue binding are hard to find.

-

Hot-glue binding machines can bind a book in less than 3 minutes, usually. Just be sure to set wider than normal margins before printing (I usually go for between 8 and 12mm for good measure) and make sure the book isn’t uncomfortably small. The minimum size should be considered in relation to the reader’s hands, how they grip the book and turn the pages, and how much effort will be needed to hold the book open in order to read it.

-

Image: A hot-glue bound book held open with one hand

-

-

digitising/printing[edit]

-

see also understanding texts, reprinting, republishing

-

Most people I know prefer to read off paper. The arguments for the printed text usually are about exhaustion, e.g. “I get tired reading from a screen”, lack of retention, e.g. “It’s proven that people remember things they read on paper better than on screen”, and in the circles I tend to run in, a sentimentality pervades, nostalgic for the haptic experience that reading from printed books brings.

-

We expect acceleration from digital technologies. The cultural significance of new media is bolstered through remediality, which is its refashioning through the lens of old media[1]. Skeuomorphic design brings us the texture of paper on a screen. Hayles argues for intermediality, the interpretations between, and the coexistence of all media, including printed and digital texts.[2]

-

Digital text is fraught with trauma, underpinned by the possibility of fragmentation. Text that is to the reader fully searchable and copy-pasteable is also text that threatens to come apart. Text that is less of an object, and more a process, often not residing in any one place in a computer file system, assembled dynamically, “on-the-fly”. Printed text, by contrast, reassures us by way of its indelibility.

-

Image: The physical bootleg library contained in a disused champagne crate, and the digital bootleg library running from a Raspberry Pi computer

-

-

-- ↑ Bolter, J.D. and Grusin, R. (2003) Remediation: understanding new media. 6. Nachdr. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

-

-- ↑ Hayles, N.K. (2005) My mother was a computer: digital subjects and literary texts. Chicago London: The University of Chicago Press.

-

-

-

producing texts[edit]

-

see also annotating, glossing, understanding texts

-

Historically, the word “text” comes from the Proto-Indo-European word teks-, meaning “to weave, to fabricate, to make; make wicker or wattle framework”. The written word is a text, and so is a conversation, both represent the exchange of shared concepts woven into the fabric of communication. There is also an exchange between written and spoken texts; discussions which influence writing, and writing which sparks conversations.

-

The digital library creates texts through its catalogue, where the metadata for each entry comprises a paratext[1] that not only adds meaning to the core text, but also influences how a reader will discover it in the collection by fields such as tags and description. Metadata which is downloaded and entered automatically comes from online commercial sources has a particular promotional tone. Those who write metadata should do so subjectively; descriptions based on personal significance represent the text and the readers, equivalently.

-

The library is sustained through producing texts.

-

Image: Papyrus, an early writing surface made from woven reeds

-

-

-- ↑ Genette, G. (1997) Paratexts: thresholds of interpretation. Literature, culture, theory 20. Cambridge ; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

-

-

-

annotating[edit]

-

see also glossing, producing texts, inter-depending

-

Marks left by readers are at times recognisable as annotation; underlines, asterisks and notes scribbled in the margins that all add something to the text. Taken a step further, annotation can include metadata (information about information), which is most commonly text that describes the author and subject, and bibliographic details needed for citation purposes. Collectively, these forms of annotation indicate the presence of readers, making them visible to each other. Annotation lives in close proximity to the text. When it is separated from the text, it becomes unfixed, losing its symbolic power to remind us that other readers have also been here.

-

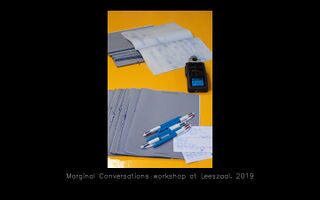

Image: Tracing paper bearing carbon-copied annotations from Marginal Conversations, a workshop first held by Simon Browne, Paloma García and Artemis Gryllaki at Leeszaal West Rotterdam, 20th June 2019

-

-

glossing[edit]

-

see also annotating, multiplying form, producing texts, writing

-

A glossary is a list of terms defined in relation to the specificity of the text. Glossaries aid reading comprehension, and also establish the presence of the readers. Glossing (from Late Latin glossa "obsolete or foreign word") was a medieval technique of adding commentaries to the main text of illuminated manuscripts. Glossators would add small handwritten notes and illustrations in between the lines and in the margins. Reading between the lines opened the text up for various interpretations, and illustrations served as mnemonic aids to assist readers to recall information. [1]

-

The texts written on these cards constitute a glossary which defines the tasks of the Contingent Librarian.

-

Image: A glossed manuscript of a late-thirteenth-century Latin translation of a medical work by Hippocrates

-

-

-- ↑ Hobart, M.E. and Schiffman, Z.S. (1998) Information ages: literacy, numeracy, and the computer revolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

-

-

understanding texts[edit]

-

see also human writing, machine writing, producing texts, technologising the word

-

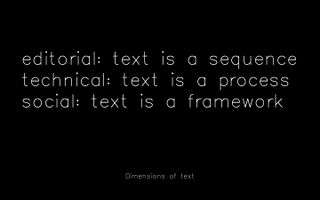

What makes up a text depends on perspective and overlapping dimensions of text; editorial, technical and social.

-

The editorial dimension; a sequence. A line of characters and spaces, the particular order that the writer sets these in. Text becomes an object, a carrier of thoughts and feelings, something that can be sent back and forth between participants in a conversation.

-

The technical dimension; a process. Cybertexts and “ergodic literature” require non-trivial effort to read[1]. Examples of this are MUDs (multi-user dungeons/domains/dimensions), which are real-time virtual worlds in which the players construct the story on-the-fly, and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves[2], a printed novel that defies a linear narrative structure through its cybertextual materiality.

-

The social dimension; a framework, a network of texts that elicit further texts.

-

The library is a collection of texts; not just books, but also files, metadata, scripts and the processes that determine how they are used, and the readers who use them.

-

Image: A spread from Danielewski’s House of Leaves

-

-

-- ↑ Aarseth, E.J. (1997) Cybertext: perspectives on ergodic literature. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

-- ↑ Danielewski, M.Z. (2000) Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of leaves. 2nd ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

-

-

-

including/excluding[edit]

-

see also making it public/keeping it private

-

Inclusion and exclusion are not just processes that occur when books arrive in the library. They are recurring, procedural, practical actions executed throughout the library’s lifetime. It comes down to the issue of space quite rapidly. With too many books, certain brutal decisions may have to be made to retain or dispose of the surplus.

-

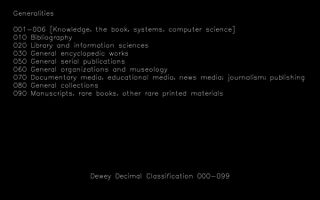

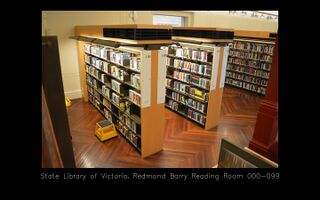

The results of including and excluding are visible in the catalogue and classification system adopted by the library, defining the particular interests of the library.

-

Inclusion also plays a part when considering how public or private the library is, and how its membership is formed. There are several layers of privilege (and accompanying responsibilities) that can be given, from anonymous guest, to registered user, to administrator. Users who have administrative privileges may add new users and bestow (or revoke) freedoms and responsibilities.

-

Image: A membership card for the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, the national library of the Netherlands

-

-

administrating[edit]

-

see also including/excluding, inter-depending, open-sourcing, trusting

-

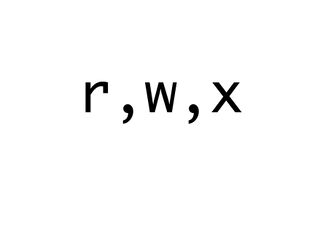

An administrator has authority to make modifications to the infrastructure of the library. Every registered user of the library is also an “admin”. With this responsibility, comes great power. An admin may delete user accounts, or take down the entire library if they wish. But they can also make registered accounts for other users, and choose to bestow the same privileges, or not. The library is open.

-

Image: Characters representing read (r), write (w), and execute (x) permissions in UNIX and UNIX-like systems

-

-

indexing[edit]

-

see also human reading, inter-depending, scanning

-

Most books contain an index. Most books are also indexed in some type of cataloguing system, to present the collection and inter-relationships between the texts contained within, and those outside of the library. This set of cards is an unbound index, which can be reshuffled, added to and reduced as the reader pleases. Reducing a text to an index opens it up for the reader to complete it as they read, drawing on what they have read before and creating a mental network of associations. A book is a hyper-index, forever pointing outwards to other books, libraries, readers and writers. I use my index finger to trace over the text, moving down the page as my eyes scan for keywords.

-

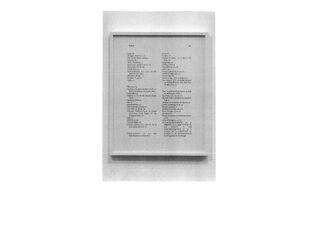

Image: Alejandro Cesarco, Index, exhibited at Witte de With Contemporary, September 2019-January 2020

-

-

making it public/keeping it private[edit]

-

see also human reading, inter-depending, scanning

-

The library depends on its public, just as the public depends on the library. Sharing of texts is the heart of library culture. A completely private collection lacks sociability. Libraries that operate outside of the law (shadow/extra-legal/pirate/+++) also depend on tactics to survive, such as password protection and invite-only systems for registering new users. In this context, publishing is not broadcasting, scattering seeds of information widely to encourage maximal distribution. The public sphere created by the library is limited by necessary measures designed to sustain it.

-

Image: Chained books at the medieval Hereford Library, an illustration from Streeter, B. H., (1931) The Chained Library; A Survey of Four Centuries in the Evolution of the English Library, B. Franklin : New York [1970]

-

-

inviting[edit]

-

see also administrating, inter-depending, trusting

-

Invitations to join the library are made through private channels of communication; direct messages, personal emails with no-one cc’d or bcc’d, private conversations held in intimate spaces, small printed cards passed by hand. Everyone is welcome to join, but the library does not require everyone to be a member in order to operate.

-

Image: A6 cards, invitations to use the bootleg library

-

-

making public[edit]

-

see also consulting, inter-depending, meeting in small rooms, in small groups

-

Making something public, and making publics. Matthew Stadler, writer and co-founder of the federated publishing network Publication Studio, makes a distinction between publishing and publication. For Stadler, publication happens not only through sharing texts, but also “setting up the circumstance through which we can talk and debate them, together”.

-

Publishing survives through publication, which is the necessary creation and maintenance of the space created for a public; to read, to share texts, to discuss and publish them. Publication continues after the event of publishing.

-

Image: Still from What is Publication?, a talk by Matthew Stadler, writer and co-founder of the federated publishing network Publication Studio, available at https://vimeo.com/14888791

-

-

keeping private[edit]

-

see also trusting, networking

-

All that I did was click a button and switch on the content server. The library was automatically assigned a dynamic IP address, followed by a colon and a port: 8080. Type http://145.131.24.139:8080 into a browser, and you’d arrive at the library, no problem. But you had to already be on the local network; you couldn’t access it from the outside. And the IP address could change without warning, as dynamic IPs often do.

-

A sequence of digits is not nearly as memorable as a domain name. And paradoxically, we expect stability from a digital environment that is quite dynamic and in flux. Trust erodes at every extra click, every retyped URL. Accessibility is tantamount to existence. If you can’t access it, it doesn’t exist.

-

8080 is for personally-run web servers. It’s called 8080 because it relates to port 80, the port that HTTP is served over. But ISPs regularly scan for HTTP requests including port 8080, to see if there is any illegal traffic occurring over the network, so it’s best to set it to a custom number (there are 65535 potential ports to use).

-

The library is now accessible from the outside over a VPN, and the page is HTTP password-protected. On arrival at the URL enter the following user name and password.

-

Image: Poster announcing the bootleg library, Piet Zwart Institute, July 2019

-

-

trusting[edit]

-

see also administrating, making public, keeping private

-

The library operates outside of legal boundaries that see knowledge as private property. As such, it requires protection from those that wish it to cease and desist. Invitations to join the library are made through personal correspondence and printed matter, in the form of A3 sized posters, and A6 sized cards, like the very one you’re reading right now. Handing a printed card with login details to an interested reader is an act of trust. The card, a pocket-sized object made with care and attention which is passed from hand to hand, engenders a certain kind of intimacy, as opposed to the brute act of spamming a mailinglist.

-

Image: A6 card, obverse and reverse, announcing the first bootleg library sessions, Piet Zwart Institute, December 2019

-

-

networking[edit]

-

see also consulting, inter-depending, making public, meeting in small rooms, in small groups

-

Networking is not a dirty word. I’m not talking about networking as schmoozing, rubbing elbows with those you wish to impress, handing out business cards like there’s no tomorrow. I mean forming networks of one’s own[1], within which the library can take shape and survive. Maintaining these networks ensures that the space for publication is available.

-

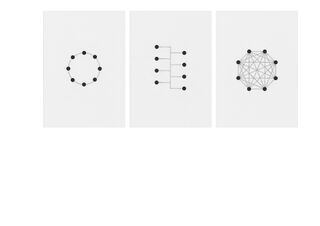

Image: Network topologies, ring, bus and mesh

-

-

-

meeting in small rooms, in small groups[edit]

-

see also administrating, consulting, making public

-

The library collection is intentionally small; it does not wish to be everything to everyone. Focused library sessions are held regularly, and informally, with participants free to come and go as they please. The sessions do not require registration, and make no demands on participants. The result is often a small group of session attendees, who can offer personal insights and opinions in an intimate setting. It is more beneficial to the library’s development to have a conversation between a small number of participants than to lecture to a crowd.

-

Image: bootleg library session at Varia, A Collective-space for Everyday Technology, Rotterdam, 26th January, 2020

-

-

consulting[edit]

-

see also administrating, making public, networking, uploading

-

The library is for all, and made by all. There is no singular embedded librarian, because everyone is a librarian, and the library is everywhere. I’m not interested in developing the “perfect” system in isolation and then dictating how it should be used, I’m interested in asking how people want to use systems, and developing them together. Technical development is ongoing in line with feedback from bootleg library sessions.

-

Image: bootleg library session at Onomatopee Projects, Eindhoven, as part of Meeting Grounds, 6th March, 2020

-

-

open-sourcing[edit]

-

see also diversifying through use, editing, networking, multiplying form

-

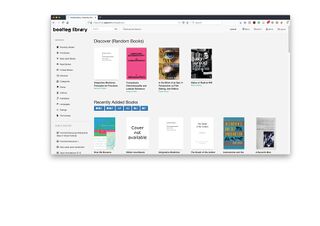

Open-source means exactly that; the source code is open for anyone to copy, modify and distribute it. The library is running on the open-source software Calibre, and is accessed through a browser using calibre-web, a web-app for ebooks stored in a Calibre database. It’s important that the library software is open-source, as this empowers us to own and modify it to suit our particular needs and interests. Technology and culture exist in a dynamic interplay, shaping and being shaped by each other.[1]

-

The notion of open-source can be extended to books as well; already there is the “public domain” (works that are outside of the bounds of copyright law, and therefore fair game) and “fair use”, which allows works to be used without asking for permission from the copyright owner, for the purposes of commentary, criticism and parody. In addressing the accessibility needed for a true knowledge commons to be protected, copyright laws are flawed to begin with as they assume that knowledge is private property.

-

Image: Screenshot of calibre-web interface

-

-

-- ↑ Hobart, M.E. and Schiffman, Z.S. (1998) Information ages: literacy, numeracy, and the computer revolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

-

-

inter-depending[edit]

-

see also diversifying through use, editing, multiplying form

-

The library is a collection of texts and the readers collected around them. Nothing comes from nothing, everything comes from somewhere, something or someone. Authors are dependent on other texts, writers, and readers. I write this text using borrowed words. As a legal, economic and institutional construct[1], authorship is problematic; current publishing models see texts as the intellectual property of authors possessed with “originality”. This originality is a myth; each text is layered in dependencies.

-

Image: An author signing a book

-

-

-- ↑ Weinmayr, E., ‘Confronting Authorship, Constructing Practices (How Copyright is Destroying Collective Practice)’ in Jefferies, J. and Kember, S. (eds.) (2019) Whose Book is it Anyway?: A View from Elsewhere on Publishing, Copyright and Creativity. Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/OBP.0159

-

-

-

proprietorising[edit]

-

see also keeping private

-

Information, in the form of descriptions that abstract themselves from the flux of common experience, is owned by private individuals or companies. Information is property, under the law. But laws should reflect the interests of the public. The “public interest” for individuals to profit from their (and other’s) labour competes against another more public, public interest, one which sees information as common property, or one that rejects any notion of information having proprietary substance. The word “information” is related to both the Latin verb informare meaning “‘to shape’, ‘to form an idea of’, or ‘to describe’, and its cognates from the substantive “forma”, which was used meaning ‘character’, ‘form’, ‘nature’, ‘kind’, and ‘manner’”[1].

-

Description seems to be the primary function of this word “information”, giving shape to experience; the very stuff of language and communication. Information has a social interest. It follows then that the most beneficial use of information would be one that serves the social good. The collective, social act of sharing information should not be trumped by individual financial interests. Never trust a corporation to do a librarian’s job.

-

Image: Headquarters of The Internet Archive, San Francisco, USA

-

-

-- ↑ Hobart, M.E. and Schiffman, Z.S. (1998) Information ages: literacy, numeracy, and the computer revolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

-

-

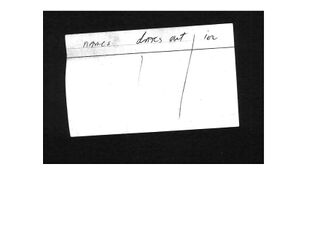

professionalising[edit]

-

see also administrating, making public

-

In order to give an appraisal of the necessity for professionalism within librarianship, first the concept of “professional” must be unpacked. Professional in what sense? The most generic definition of being able to profess a skill is the first that comes to mind. This seems hardly a thing to argue against, as the particular skills of professional librarians are certainly called for in most cases. If we take another generic assumption that the profession of a librarian revolves around the mores of making information accessible, then this invites questions about associations between moral behaviour and professionalism. All this aside, what I can say is that professional librarians are not seriously threatened by the amateur librarians, operating from a distance. The threat comes from much closer for them; budget cuts that cripple and close their libraries, policies driven by the encyclopedic expectation that digital volumes of data inspire.[1]

-

Image: A makeshift library checkout card, usually placed in a pocket in the back of a book

-

-

-- ↑ Murray, J.H. (1998) Hamlet on the holodeck: the future of narrative in cyberspace. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

-

-

-

amateuring[edit]

-

see also making public, professionalising, republishing

-

Amateur librarianship happens whenever texts are shared informally. An amateur (from French, meaning “one who loves, lover”) acts out of love (rather than motivated by prestige, or money); there is not often a conscious decision to be an amateur anything. Instead, we often see the word “amateur” as a negation or lack of professionalism. A rising imperative emerges, for amateurs to take up the task of librarianship. The 19th century model of the public library that spread throughout the U.K. and the U.S.A. was an exemplar of social democratic values. Such libraries are now under threat. So, sometimes in response, but often without thought of the legal consequences, amateur librarianship happens in small, quiet ways that are usually mundane; passing a USB drive around, emailing a link or a file. I thought you should read this.

-

Image: USB drives as libraries

-

-

reading/writing[edit]

-

see also editing, typing

-

Reading and writing are interdependent; a written text exists to be read, and is based on a history of reading comprehension and processing, from the early stages of literacy (developing ability to recognise separate characters), to reading complex texts that become references for things we write. In an operational sense, we also read what we write, as we’re writing it. So, the process of writing is combined with reading, and both gestures can be found in another word that blends the two acts together: editing.Writing, reading, editing; growing a tree while making a chair from its wood to sit on.

-

Image: Simon Browne, timed writing/editing experiment using Etherpad, collaborative text-editing software, 2018. The bars at the top indicate separate durations of 5-minute writing, and 3-minute editing periods

-

-

reading[edit]

-

see also technologising the word

-

Although literacy is the ability to read and write, an illiterate person is often described as not being able to read, rather than write. This is because the receptive skill of reading precedes the productive skill of writing. We write in response to the information we receive. Reading requires a command of the language the text is produced in, as well as a capacity to store this information in a durable medium; a book, a file, a tape, and so on.

-

Media theorist Friedrich Kittler said that, historically, reading functioned as “hallucinating a meaning between the lines”[1]. This hallucination was exemplified by poetry, whereby the poet intended to induce in the reader into a state of shock with words. Kittler argued that the harnessing of electricity was the end of such hallucinations; as soon as optical and acoustic data could be electronically stored, we no longer needed our memory, and the realm of the dead was no longer in written words. The gramophone, typewriter and film produced new ways of writing and reading texts.

-

Image: Reading-and-writing-at-the-same-time, diagrammed in The Principles of Psychology, William James (1890)

-

-

-- ↑ Kittler, F.A. (2012) Literature, media, information systems: essays. Critical voices in art, theory and culture. Johnston, J. (ed.). London New York: Routledge.

-

-

-

skimming/scanning[edit]

-

see also human reading

-

Reading comprehension relies on the twin skills of skimming and scanning, often done together. Depending on what the function of the text is, one skill will be used more than the other. It would be foolish to skim a contract without reading the small print carefully. And if you don’t skim a newspaper article to get the gist of it, scanning for details is meaningless.

-

Image: A reader highlights text while skim-reading in order to improve retention and to create a hierarchy in a text, applying a style that can be efficiently scanned for at a future time

-

-

human reading[edit]

-

see also technologising the word

-

There are many different reasons why you might read something, but essentially, reading involves skimming (reading to get the main idea of a text) or scanning (looking for specific information in details). This often happens in tandem—skimming the catalogue to see what the interest of the library is, and then scanning to see if a particular text has been included—and has relations to other modes of information retrieval, e.g. browsing/searching.

-

In 1977, while facing a skeptical audience in a Q & A session broadcast live on Australian television, Marshall McLuhan argued “the word read means to guess – look it up in the big dictionary. Reading is an activity of rapid guessing because any word has so many meanings – including the word reading – that to select one in a context of other words requires very rapid guessing. That’s why a good reader tends to be a very quick decision-maker.”[1] This is very true of human reading, where multiple interpretations lead to various equivalent understandings of a text, but false when applied to machine reading, which only operates with predefined ways of interpreting text.

-

Image: "the word read means to guess" A quote from Marshall McLuhan during a live television broadcast, 1977

-

-

-

skimming[edit]

-

see also human reading

-

Skimming is reading for the main meaning of a text, reading between the lines in a semi-distracted state. A way to get the gist of a text quickly, flipping pages, jumping pages with the spacebar, infinitely scrolling. Just like skimming stones over water, the eyes jump in saccades over the surface of the text.

-

Many prefer to read from paper than from a screen. Who hasn’t heard complaints that reading from a screen is tiring, especially when you just want the gist of a text? Sometimes online articles are accompanied by information about how long it will take to read them. Estimated reading time 6 mins. Max word count 400-600 words.

-

Image: Speed reading

-

-

machine reading[edit]

-

see also scanning

-

Machines can read text, and process it in complex ways. Code may contain instructions for a computer to read a file, so that its contents may be then used as part of a program. An example of this in practice is in the catalogue details of books in the library (title, author, description, publisher etc), which can be downloaded rather than manually written. This involves communication between systems to search their databases; for example, taking these details from another source, such as https://books.google.com or https://goodreads.com.

-

Books can also be checked in and out of libraries by a variety of machine reading methods such as barcode scanning, or using RFID (radio-frequency identification) chips inserted into the cover.

-

Image: An RFID tag; an object often contained within the cover of a public library book to track when it is checked in or out

-

-

scanning[edit]

-

see also human reading, machine reading

-

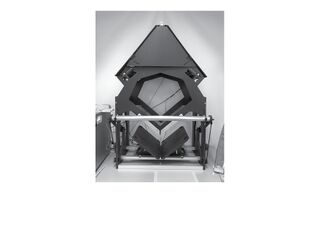

Scanning is reading for particular details (such as names and numbers) by running one’s eyes over every word in a line. Sometimes I find myself using my index finger to guide my eyes when scanning a printed text. With a computer and full-text search capabilities, control-f helps find instances of a particular word or phrase.

-

Scanning is also a way to process printed matter so that it may be electronically archived, modified and distributed. A bookscanner is the tool of choice for many archivists. It has two cameras, one to capture the odd pages, and one for the even pages. Most bookscanners consist of a system of pulleys which allow the book to be raised to two perpendicular sheets of glass, laying the pages flat and ensuring the focus is correct. It’s quite a workout, and is usually reserved for books which are difficult to find in digital format. Essentially the bookscanner takes two photographs, one each for the even and odd sides of a spread. So the sequence goes; flip, click click, flip, click click, and so on, and so on. Next, these images must go through a variety of processes to produce a digital book; rotating, cropping to the size of the page, merging into a single PDF. Ultimately, the most useful digital books include a digital text layer generated by OCR (Optical Character Recognition) software, making the text searchable and copy/pasteable.

-

Image: An archivist bookscanner

-

-

writing[edit]

-

see also technologising the word, producing texts

-

Writing is a technology which transforms cultures, particularly from pre-literate perceptions of memory as a commemorative act bound to the flux of human experience, to post-literate thinking of it as containers within which to store information. The invention of the Greek alphabet, with its introduction of letters representing vowels[1], connected speech with a form of its material representation. This technological development resonates with how we perceive oral communication—thinking of spoken language through the lens of literacy; as discrete, easily divisible units, like printed words punctuated by neat spaces. It all falls apart when speech-to-text transcription software “doesn’t work” (meaning that it works in ways that we do not expect). The result is that speech, essentially the long continuous sounds that we make with our mouths, tongues, teeth, lips and throat, comes out as gobbledygook on the screen.

-

Writing is a fundamental part of the library. Not only in the written texts it contains, but also in the texts it produces; metadata (information such as author, title, subject, description, publisher, etc), annotations made by readers, readers made by readers, correspondence between the users about the texts, which form a dialectical synopsis. The library is sustained through producing texts which argue for its legitimacy by representing the readers who use it.

-

Image: Very early Greek abecedariums, inscriptions of the alphabet in order, typically used as a practice exercise in learning writing, from Drucker, J. (1999) The alphabetic labyrinth: the letters in history and imagination. London: Thames & Hudson

-

-

-- ↑ Hobart, M.E. and Schiffman, Z.S. (1998) Information ages: literacy, numeracy, and the computer revolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

-

-

technologising the word[edit]

-

see also reading/writing, understanding texts

-

According to the philosopher Vilém Flusser, history—in the traditional sense of a record of events—begins with writing. As such, writing created a linear, historical consciousness. This allowed us to see events as part of a process that is manipulable by humans, outside of divine intervention. Before the technology of writing, a propriocentric notion of the world dominated human consciousness; perceived through the senses, immediate and without what we think of as history, which comes from the ability to store memory in texts. Flusser adds that “Those who use texts to understand the world, those who ‘conceive’ it, mean a world with a linear structure”.[1]

-

In pre-literate cultures, such as in Ancient Greece, songs were stitched together into rhapsodies.[2] Before literacy, texts existed as oratories, plays, epics, proclamations and dialogues; mostly oral forms. The nature of text is to knit together communication. In literate cultures texts become textiles, tapestries that form cultural narratives.

-

Image: The Rosetta Stone, a tablet discovered in 1799, inscribed with three versions of a decree written in Ancient Egyptian and Ancient Greek

-

-

-- ↑ Vilém Flusser ‘The Future of Writing’, from Flusser, V. and Ströhl, A. (2002) Writings. Electronic mediations v. 6. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

-

-- ↑ Ong, W.J. and Hartley, J. (2012) Orality and literacy: the technologizing of the word. Orality and literacy. 30th anniversary ed.; 3rd ed. London ; New York: Routledge.

-

-

-

human writing[edit]

-

see also typing

-

Writing “by hand” is how we most often think of the act. The hand is symbolically connected to the act of writing, to the extent that we still use icons of the hand-held utensils to represent it graphically—a ballpoint pen, a pencil, even an old-fashioned quill and nib, all often associated with letter-writing. Slowly, this iconography is being replaced by another symbol; the keyboard, signalling the contemporary dominance of typography on writing.

-

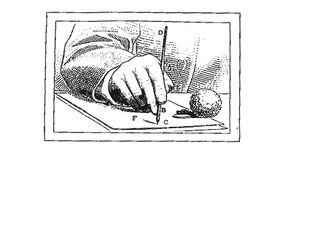

Image: ‘Proper posture for writing with pen’, from Drucker, J. (1999) The alphabetic labyrinth: the letters in history and imagination. London: Thames & Hudson

-

-

-

see also machine writing

-

It wasn’t handwriting that drove forward the technology of writing into the modern era, but type. Moveable type expanded the publishing capabilities of text from a one-to-one to one-to-many model. In the late 19th century hot-typesetting machines melted pieces of aluminium and cast them into type, in order to be re-used and repeated. Input for these machines was often entered on a keyboard, which produced a perforated paper tape, a common early data storage medium. A distinguishing feature of these early typesetting machines was the ability to iterate processes by storing information in a reusable format.

-

For the keyboard, iteration operates at another level, the keys. The keyboard has its roots in moveable type, which produced “typing”, or using a discrete set of components that could be rearranged in infinite combinations. From iteration comes automation; “typewriters”, which emerged onto the market around the same time as the phonograph, were often advertised as a product that enabled “automatic writing”.

-

Image: The first commercially-produced typewriter, the Hansen Writing Ball, from Kittler, F.A. (1990) Discourse networks 1800/1900. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press

-

-

machine writing[edit]

-

see also editing

-

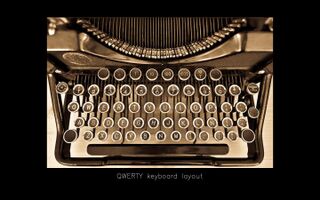

This text is being written on a QWERTY keyboard, through a browser, using a software called “Etherpad” that records every changeset—every typed key of the characters that are added or deleted. The software is logging these changes fast enough that it appears to be happening in real time. I can also go back through every previous changeset to older versions with the granularity of the individual character. This is the liminal space between texts; in split-seconds of processing where human writing is manipulated by machine writing.

-

Image: QWERTY keyboard layout

-

-

searching/browsing[edit]

-

see also skimming/scanning

-

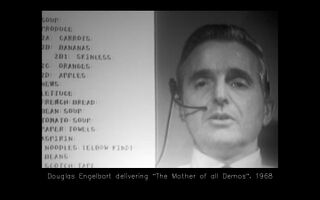

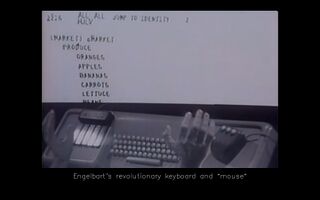

The difference between these two depends on the interface, and its seductive (or stoic) effect. The way users are affected also depends on the hierarchy of information presented, and interfaces that limit how that information is retrieved. For example, the screen, keyboard, and mouse make up the interface of the library when viewed on a desktop computer. On a smartphone, only the screen and keyboard comprise the interface. Given a mouse, a user may be more liable to pinpoint or target information. Some features are more conducive to searching, like a search bar, some more to browsing, like a scroll bar. The library can be accessed through a browser, just type hub.xpub.nl/bootleglibrary into the search bar.

-

Image: A mouse, keyboard and collaborative text-editing demonstrated in Douglas Englebart’s “Mother of All Demos”, 1968

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-