Introduction

Act 1.

Scene 1.

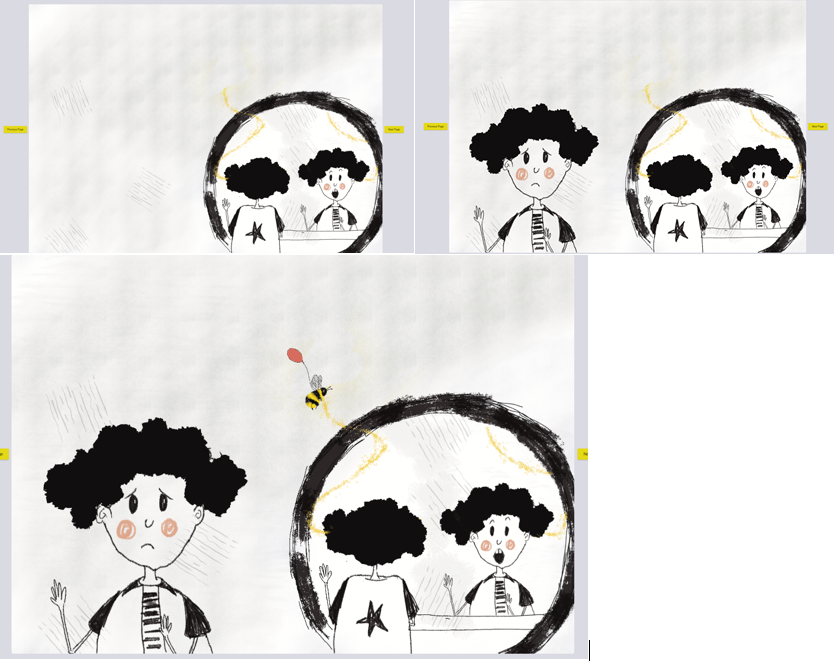

Internal. A reader holds a book in their hands. The first page of the book is opened, the reader holds it to their face and smells the paper, touches it. The book touches them back.

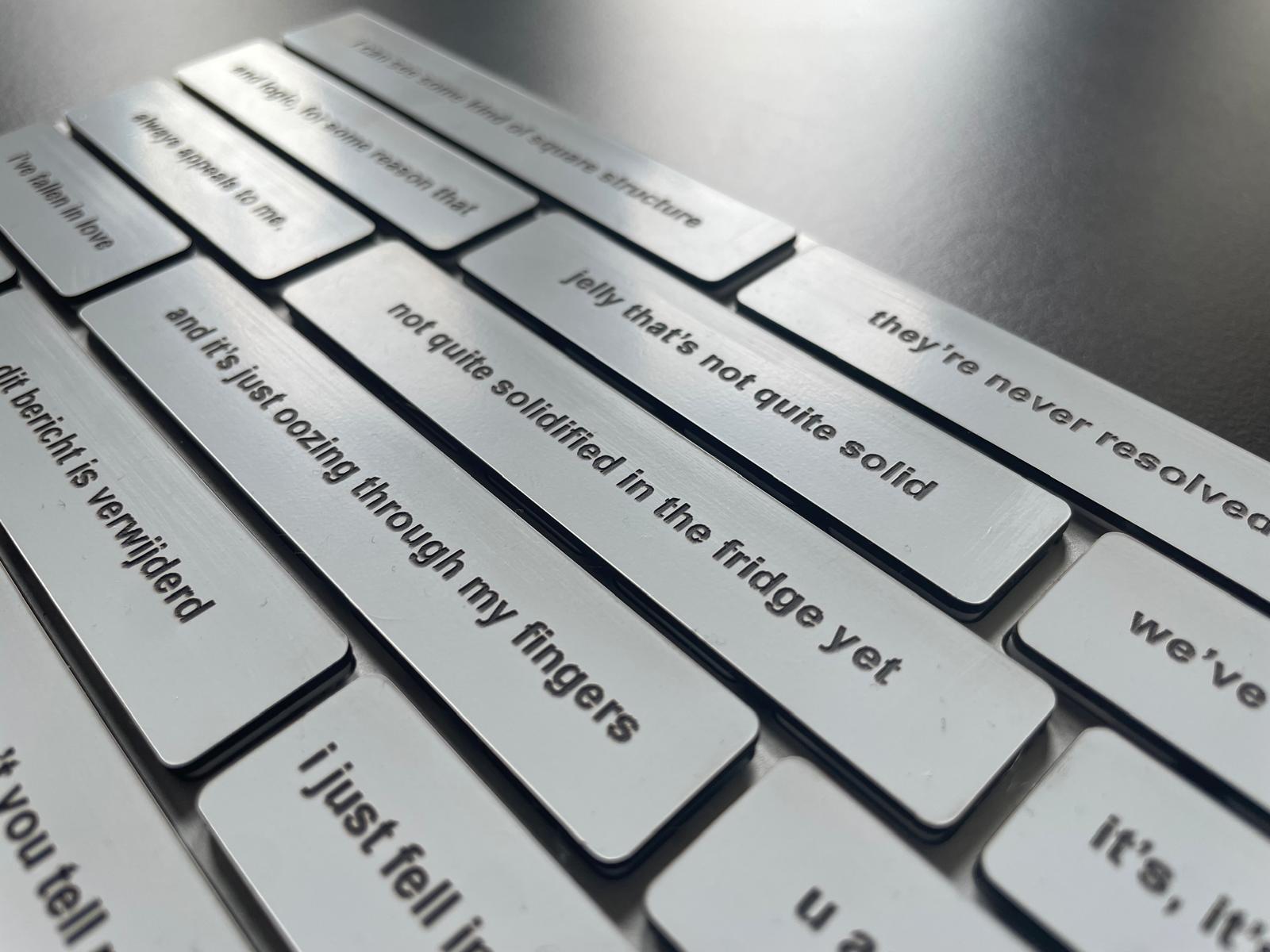

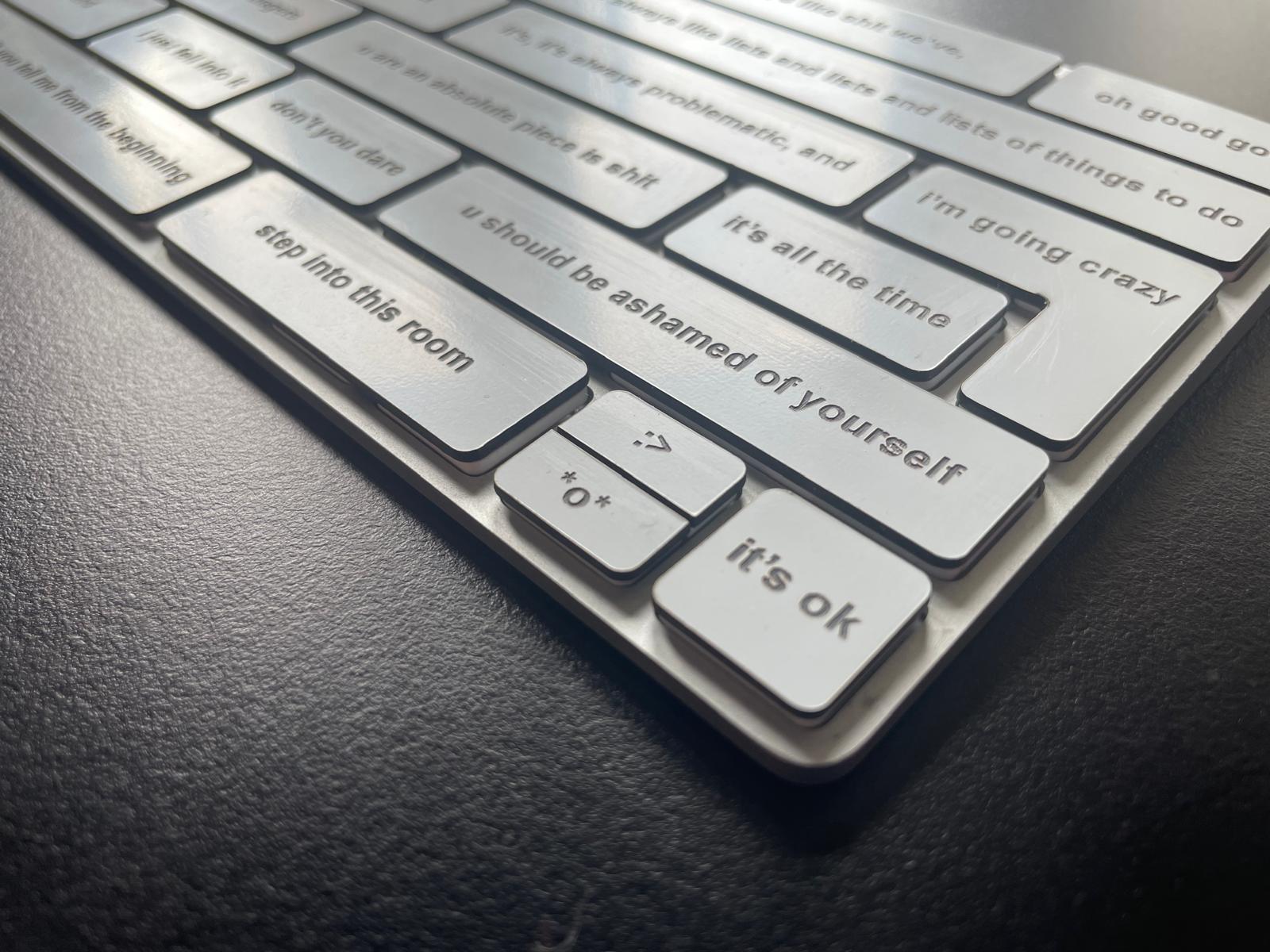

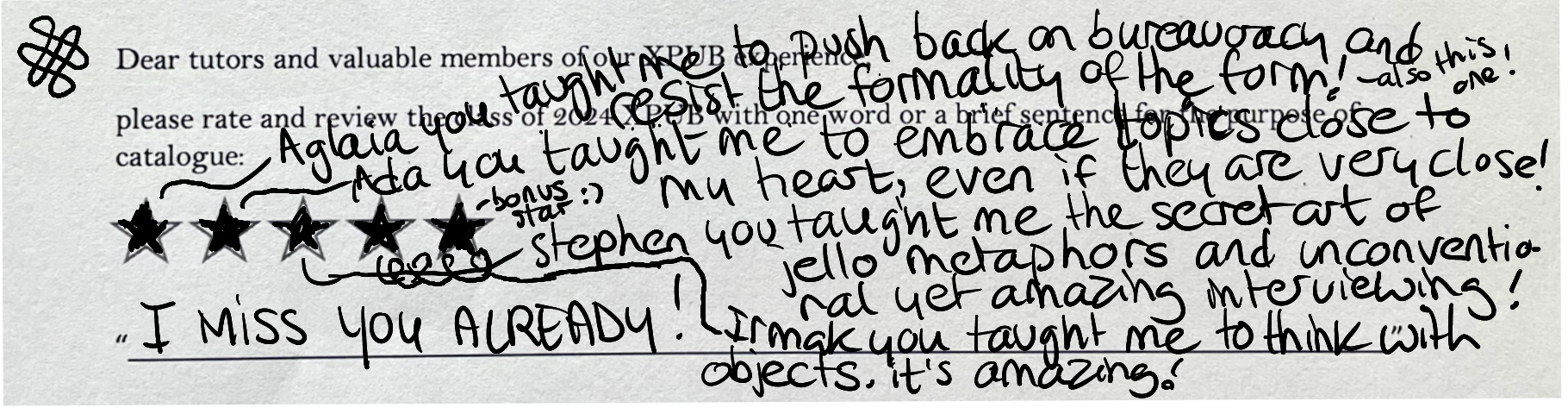

the book: (whispering in the reader’s ear) Being vulnerable means being transparent, open and brave, trusting others to handle stories with care. By publicly sharing and processing our narratives, we take ownership of our experiences while contributing to a collective voice. Even when we incorporate stories from others, our names remain attached to this collective creation: Ada, Aglaia, Irmak, Stephen. We have created interfaces highlighting the balance between communal sharing, individual responsibility and awareness.

the reader: Interfaces?

the book: Interfaces are boundaries that

connect and separate. They’re the spaces that fill the void between us.

An interface can be an act, a story, a keyboard, a cake; It allows us to

be vulnerable together, to share our stories with and through each

other. I am a collection of these interfaces.

the reader: (confused) What do you mean a collection, like a catalogue?

the book: Yeah I guess. I weave the words and the works we created during…

the reader: we?

the book: …I mean the four of us, the students of Experimental Publishing at the Piet Zwart Institute. From 2022 until today, June 2024, we published three special issues together. We wrote four theses and made four graduation projects. We grew our hair out and cut it and grew it again and dyed it. We cared and cried for each other, we brewed muddy coffee and bootlegged books.

(The book tears up).

Finishing a Master’s is a bit of a heavy moment for us and this book is a gentle archive, a memory of things that have been beautiful to us.

the reader: (sarcasm) do you have a tissue, im soooo touched.

the book: malaka, just read me.

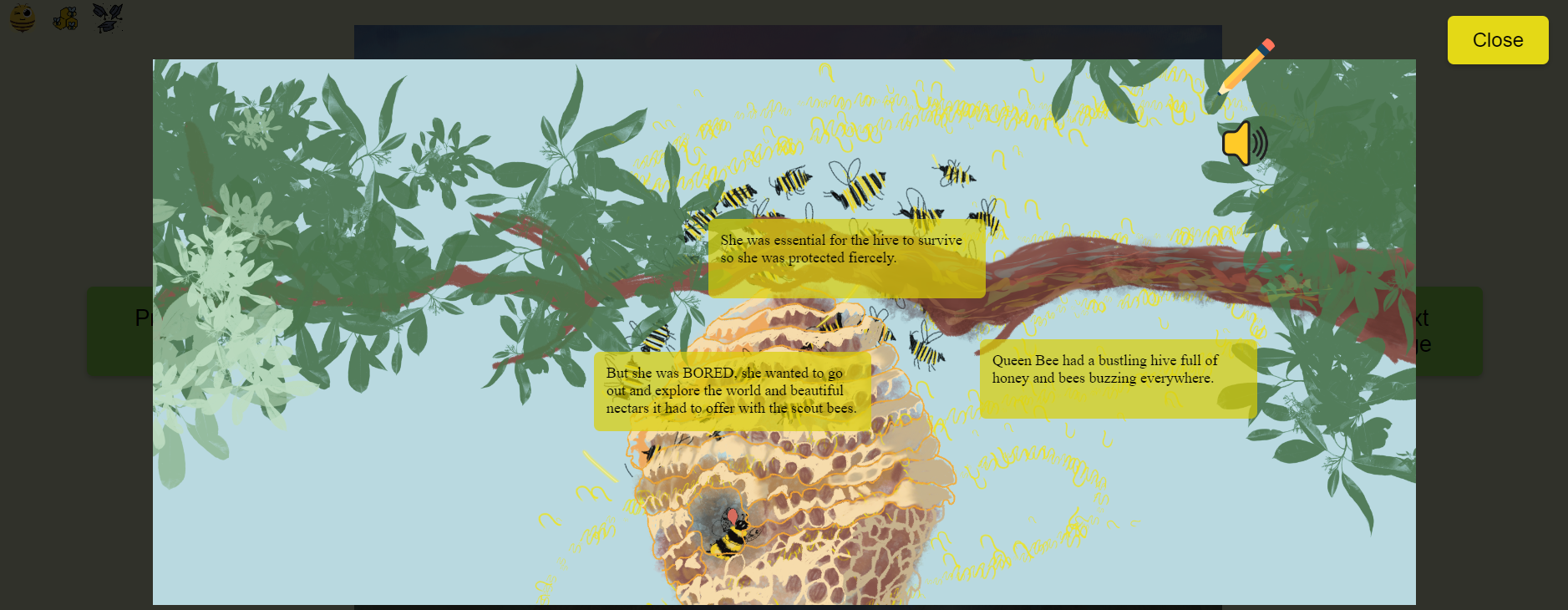

<?water bodies>

divergent digital intimacies

Water, stories, the body,

all the things we do, are

mediums

that hide and show what’s

hidden.

(Rumi, 1995 translation)

꙳for you

All intimacy is about bodies. Is this true? Does it matter? I doubt it. Do you know? Let’s find out, maybe.

Once, I thought that everything in the world was either one or zero and that there was a harsh straight line between them. Then I found out you could step or hop across the line, back and forth, if others showed you how. Today, I am no less binary, no less interested in dichotomies, but I am willing to dance through them if you are too. Can we dance these dichotomies together, embracing the contradictions of the virtual and physical, the comfortable and uncomfortable, intimate and non-intimate? I can’t do it alone, the subject is too heavy and the binary is too 1011000. I won’t ask you to resolve these contradictions, I have no desire to. Instead, I hope we can cultivate the tension and tenderness inherent in holding together incompatible truths because both prove necessary.

To dance through these dichotomies I will start in a specific position, growing from Donna Haraway’s in ’A Cyborg Manifesto”. In her essay, Haraway explores the concept of a cyborg as a rejection of boundaries between humans, animals, and machines. A symbol for a feminist posthuman theory that embraces the plasticity of identity. Before she does all this dancing, however, she takes a strong stance of blasphemy. She engages seriously with traditional notions of feminism and identity but with irony, not apostasy, which is to say without full rejection—without unbelief. My position as I jump will be the same as hers, ironic faith. My mocking is grave but caring and my primary aim is for us only to spin fast enough not to see the line anymore, while still being able to see the binaries. It won’t be an easy dance for us but I will do my best to keep softening for you, I promise.

I will show you a digital body, make it comfortable and then uncomfortable, lightly intimate, and richly intimate. I have my own story, my own digital body, of course. This is where I take my second stance, however. This time, the position is Lauren Berlant’s, from ‘The Female Complaint’. The book places individual stories as inescapable autobiographies of a collective experience and uses the personal to explain an intimate general experience. In our story, the difference between my body and the collective digital body is unimportant, I hope you see that. I will tell you my story if you know how to look, but I will tell you through the stories of many others who shared them with me. I have no other choice, every time I have tried to tell this story a chorus of voices has come out.

Some of the stories I will tell you will carry memories of pain; physical and emotional. I will keep holding you while you hear this, but your limbs may still feel too heavy to dance. In that case, I give you my full permission to skip, jump, or lay down completely. This is not choreographed and I care deeply for you.

I love you and hope you see what I saw in these stories.

Safe dreams now, I will talk to you soon.

0. DIGITAL BODIES

“I think the worst must be finished.

Whether I am right, don’t tell me.

Don’t tell me.

No ringlet of bruise,

no animal face, the waters salt me

and I leave it barefoot. I leave you, season

of still tongues, of roses on nightstands

beside crushed beer cans. I leave you

white sand and scraped knees. I leave

this myth in which I am pig, whose

death is empty allegory. I leave, I leave—

At the end of this story,

I walk into the sea

and it chooses

not to drown me.”

(Yun, 2020)

a. what is a digital body?

A digital body is a body on the Internet. A body outside the internet is simply a body. On the internet, discussions about corporeality transcend the limitations of physicality, shaping and reshaping narratives surrounding the self. This text explores the intricate dynamics within these conversations, dancing at the interplay between tangible bodies and their digital counterparts. The construction of a digital body is intricately intertwined with these online dialogues, necessitating engaged reconstructions of the narratives surrounding physical existence. Yet, the resulting digital body is a complex and contradictory entity, embodying the nuances of both its virtual and tangible origins.

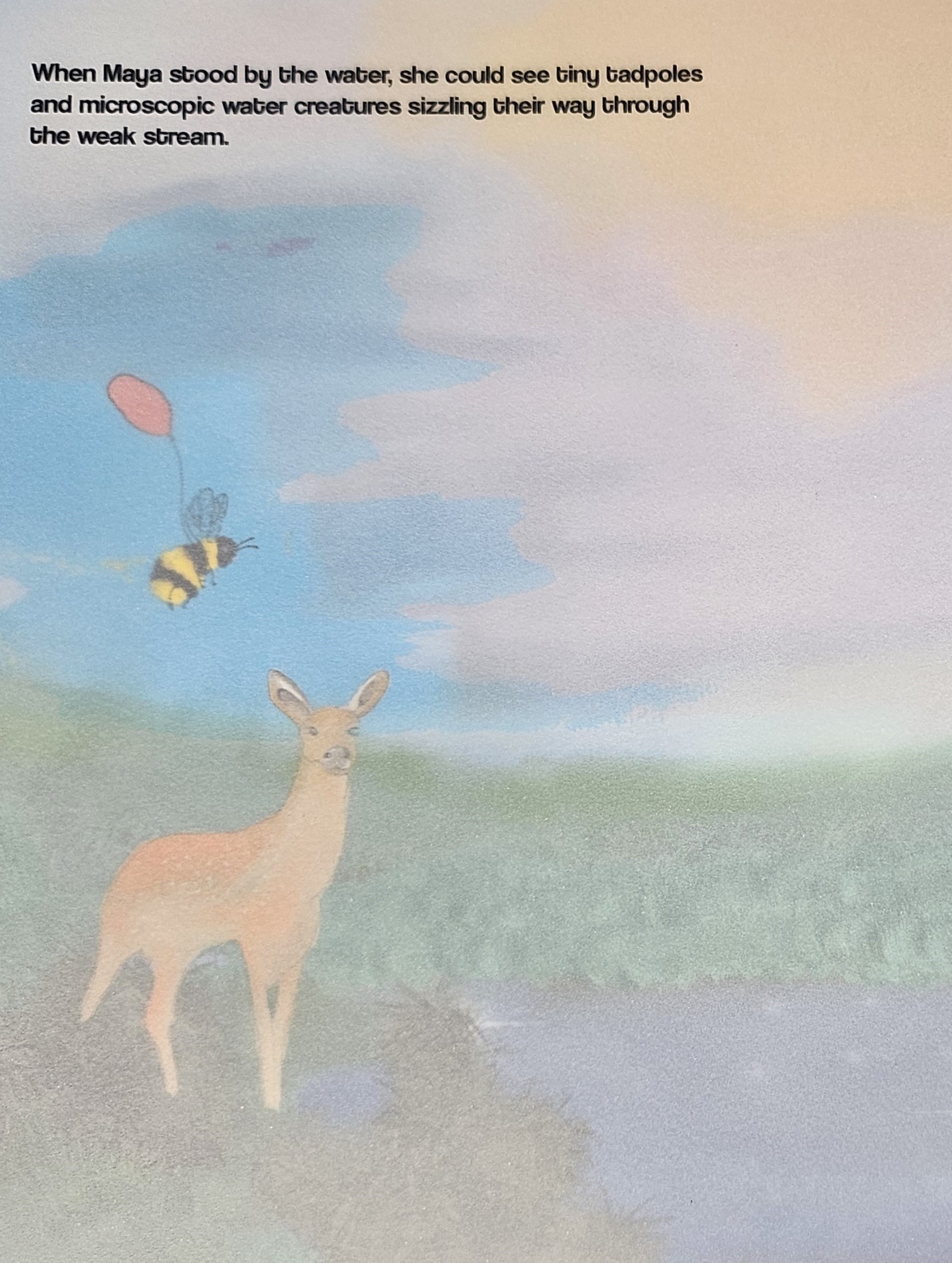

There is a specific metaphor that would allow us to better carry these contradictions as we further explore digital bodies. Do you remember that dream you had about deep ocean pie? Allow me to remind you.

You were walking on the shore, slowly, during a summer that happened a long time ago. Your skin was warm and you could feel the wet cool sand sticking to your feet. The gentle lapping of the waves washed the sand away as you walked towards the ocean. You stepped, stepped. Then dove. Underwater, the sea unfolded deeper than you remembered. It was a vibrant display of life: bright schools of small fish, and tall colorful, waving corals. It looked like that aquarium you saw once as a kid. Your arms moved confusingly through the water as if you were wading through a soup or were terribly tired. On the sandy ocean floor, you saw a dining table. It had a floating white tablecloth, one plate, a fork, and a pie in the center of it, on a serving dish. You sat on a chair but could not feel it underneath you. You ate a heaping slice of pie. It had a buttery-cooked carrots filling. You woke up. In the world, the sun was still timid and your bedroom thick with sleep. What a weird dream. You rubbed your face, sat up on your bed, and drank the glass of water next to you. You felt full, as if you just ate a plateful of carrot pie.

There were two bodies in this story. An awake one and a dream one, an ocean one. In dreams, bodies have their own set of rules, often blurring the boundaries between waking and sleeping, wanting and fearing. Digital bodies are very similar to dream bodies. They exhibit a similar fluidity and abstraction, a defiance of traditional notions of physicality. They share the blurring and inherent potential nature of dream bodies. They are slower, stronger, and different. They switch and change and melt into each other, they lose and regrow limbs, they run sluggishly and fly smoothly. If we scream in our dreams, we sometimes wake up still screaming. Our waking bodies react to our dream bodies, they have the same tears, the same orgasms, the same drives.

This is a story of two bodies, same but different, influenced but not driven. A tangible body, full of fluids and organs, emotions and feelings. Cartilage, bacteria, bones, and nerve endings. A digital body, cable-veined and loud-vented, shiny and loading.

The digital body is ethereal and abstracted, embarrassing, graphic, and real but not physical.

This is the beginning.

b. body vs. computer

Framing the discourse around bodies on the internet as a clear-cut dichotomy feels clunky in today’s internet landscape. The web is today available by body, cyborg dimensions of the internet of bodies, or virtual and augmented realities, creating a complex interplay between having a body and existing online.

As intricate as this dance is now, it certainly did not begin that way. It started with what felt like a very serious and tangible line drawn by very serious tangible people; this is real life and this is virtual life. Even people like Howard Rheingold, pioneers who approached early virtual life with enthusiasm and care, couldn’t escape characterizing it as a “bloodless technological ritual” (1993). Rheingold was an early member of The Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link (Well), a seminal virtual community built in the 1980s that was renowned for its impact on digital culture and played a pivotal role in shaping what would become the landscape of the Internet. Rheingold’s reflections on his experience on this primordial soup of the Internet offer insight into the initial conceptualizations of online life by those joyfully participating.

In “The Virtual Community”, Rheingold offers a heartfelt tribute to intimacy and affection through web- based interactions which, at the time, were unheard of. He struggles in his efforts to highlight the legitimacy of his connections, finding no way to do so except by emphasizing their tangible bodily experiences. The community’s claim to authenticity thus had to lie in the physical experiences of its members— the visible bodies and hearable voices, the weddings, births, and funerals (1993).You’re dreaming again, good. Would you feel closer to me if you could hear my voice? Is my voice a sound? Could it be a feeling?

Even then, and even by people with no interest in undermining the value of the virtual, the distinction between physical and virtual was confusing. Rheingold himself reinforces the boundary of body relations and computer relations by referring to his family as a “flesh-and-blood family’ and his close online friends as “unfamiliar faces” (1993). Constantly interplaying digital connections with the physical characteristics of the kind of connections people valued before the internet.I will be honest with you, I have little patience for this recurring line of thought that seeks to distinguish people’s noses from their hearts, as if there was a physical love that is the valuable one and a virtual imaginary one that is feeble and unworthy.

In any case, his primary interest seemed to be to emphasize computer relations as valid forms of connection between bodies, not to talk of any distinction quite yet. It’s the eighties, the internet is still fresh and new and the possibility to form close relations with strangers online seems fragile and concerning yet exciting. This is the clearest the distinction between in-real-life and online has ever been and it’s still fuzzy and unclear.

At the same time and in the same digital space as Rheingold, there was another man, a digital body being formed. This is our second story, the ocean body we dreamt of earlier is now in a digital primordial soup, questioning itself and stuck between staying and leaving. In this story, its name is Tom Mandel and when he died, he did so on the Well.

Mandel was a controversial and popular figure in this pioneering virtual community. According to many other members, Tom Mandel embodied the essence of the Well—its history, its voice, its attitude. Mandel’s snarky and verbose provocations started heated discussions, earning him warnings such as “Don’t Feed The Mandel!” (Leonard, 1995). His sharp comments often stirred emotions that reminded people of family arguments, fuelling an intimacy that was characteristic of the Well: both public and solitary (Hafner, 1997).

Until 1995, Mandel had done a quite rigorous job of keeping his body separate from The Well and had never attended any of the physical in-person meetings from the community. His only references to being a body had been on the “health” online conference, where he often talked about his illnesses. One day, after nearly a decade of daily interaction, he posted he had got the flu and that he felt quite ill. When people wished for him to get well soon, he replied he had gone to get tested and was waiting for a diagnosis. This way, when cancer was found in his lungs, the community was first to know. In the following six months, as his illness progressed, the community followed closely (Hafner, 1997). They were first to know when Nana, a community member with whom he had had a publicly turbulent relationship, flew to California to marry him. The community was a witness and is now an archive of his declining wit as cancer spread to his brain and his famously articulate and scathing comments got shorter, fearful, and more tender.Initially, when a member he often argued with offered to pray for him Mandel had replied: “You can shovel your self-aggrandizing sentiments up you wide ass sideways for the duration as far as I’m concerned.” Later, as the cancer progressed: “I ain’t nearly as brave as you all think. I am scared silly of the pain of dying this way. I am not very good at playing saint. Pray for me, please.

Before he posted his final goodbye, he chose to do one last thing. Together with another member, they programmed a bot that posted randomly characteristic comments from Mandel on The Well—the Mandelbot. In the topic he had opened to say goodbye, he posted this message about the bot:

“I had another motive in opening this topic to tell the truth, one that winds its way through almost everything I’ve done online in the five months since my cancer was diagnosed. I figured that, like everyone else, my physical self wasn’t going to survive forever and I guess I was going to have less time than actuarials allocateus [actually allocated]. But if I could reach out and touch everyone I knew on-line… I could toss out bits and pieces of my virtual self and the memes that make up Tom Mandel, and then when my body died, I wouldn’t really have to leave… Large chunks of me would also be here, part of this new space.” (Hafner, 1997)

With the Mandelbot, Mandel found a way to deal with what he later called his grieving for the community, with which he could not play anymore once his own body died. By doing so, he was starting to blend the boundaries of intimacy through computers and bodies, driven by his love and grief.It’s out of care and not lack of relevance that I am not showing you Mandel’s goodbye message. It’s enough to know he was deep in the grief of having to leave a community he loved and cared for and that pain was felt in every word.

When he talked about the bot in previous messages, it sounded almost like a joke. A caring haunting of the platform, to keep his persona alive for the community in a way that could be quite horrific for those grieving. In his admission though it becomes clear that this was closer to an attempt to deal with his grief around losing the community, his unreadiness to let go of a place he loved so dearly. A place just as real in emotion, that was built in part by Mandel’s digital body and its persona.

In a tribute posted after his death, fellow Well member and journalist Andrew Leonard tried to convey his own sense of blended physicality and emotion.

“Sneer all you want at the fleshlessness of online community, but on this night, as tears stream down my face for the third straight evening, it feels all too real.” (Andrew Leonard, 1995)

c. bot-feelings

An internet body has bot-feelings if allowed to. Let me explain.

A bot functions as a different entity from a cyborg, as it does not attempt to emulate a human body but rather human action and readiness. Its role is to mirror human behavior online, simulating how a physical body might act, what it would click on, and what would it say. On social media, bots engage in a kind of interpretative dance of human interaction, performing based on instructions provided by humans.The first bot communities on the internet are now born, half- mistakenly. They are always spiritual communities posting religious images created by artificial intelligence, all the comments echoing choirs of bots praising. Amen, amen, amen. I am not naive, I know they are built by humans but it is this performance of religiosity that I am interested in, and how little humanity is shown in it. It is something else.

Unlike an internet body, which represents the virtual embodiment of a person, a bot doesn’t seek to be a person. It comments under posts alongside many other bots, all under a fake name and photo but nothing else to give the illusion of humanity. When an internet body has bot-feelings, it is a disruptive performance. They are feelings that do not attempt to be human body feelings, they exist as their own genuine virtual expression.

In “Virtual Intimacies”, McGlotten also incidentally argued that a virtual body has bot-feelings (2013). He described the virtual as potential, as a transcendent process of actualization, making it into, generally, a description of bots. Internet bodies, as virtual, would be by this understanding also charged with the constant immanent power to act and to feel like a human body. It is a constant state of becoming, of not- quite-pretending but never fully being anything either.

Most of the time we can tell disembodied bots online from tangible people and as such they have the potential to be bodies, without ever trying to be.

Of course, when McGlotten described the virtual as such he placed it in a dichotomy, once again, against the “Intimacies” which are the other side of his book. The emphasis here lies in intimacy being an embodied feeling and sense and a carnal one at that. Virtual intimacies are, by this definition, an inherent failed contradiction. However, McGlotten plays with the real and non-real in new ways, using the text to highlight how virtual intimacy is similar to physical intimacy and then, even more, blurring as he shows the already virtual in physical intimacies. Applying this to a body, rather than an affective experience, works just the same.

McGlotten uses a conceptualization of the virtual based on the philosopher Deleuze’s,A step in a step in a step, sorry. which can be used to refer to a virtual body as well. The virtual is in this case a cluster of waiting, dreaming, and remembering, embodying potential. Something that is constantly becoming, an object and also the subject attributed to it (2001). An internet body with its bot-feelings is a body in the process of being one, acting as one, an ideal of one beyond what is physical but including its possibility.

Going a step further in McGlotten’s interpretation of Deleuze, this also plays into how virtual intimacies mirror queer intimacies as they approach normative ideals but “can never arrive at them”. Both queer and virtual relations are imagined by a greater narrative as fantastical, simulated, immaterial, and artificial—poor imitations and perversions of a heterosexual, monogamous, and procreative marital partnership (2013). A virtual body is similarly immanent, with both potential and corruption at the same time. It carries all the neoliberal normative power of freedom that a queer body can carry today but also reflects the unseemly fleshly reality of having one.

This is where the story continues. The body from the dream ocean leaves the primordial soup of the internet to stage a disruptive performance. It moves from potential creation to a wild spring river. A fluid being, that exists simultaneously inside and outside normative constructions. It channels deviant feelings and transcendental opinions about the collective’s physical form genuinely as people use it to navigate their physicality. Both virtual and queer intimacies highlight the constructed nature of identity and desire. They disrupt the notion of a fixed, essential self, instead embracing the multiplicity and complexity inherent in human experience. This destabilization of identity opens up possibilities for self-expression and connection, creating spaces where individuals can redefine themselves beyond the constraints of societal expectations while still technically under its watchful eye. In essence, the parallels between virtual and queer intimacies underscore the radical potential of both to disrupt and reimagine the norms that govern our understanding of relationships, bodies, and identity. They invite us to question the rigid binaries and hierarchies that structure our society and to embrace the fluidity and possibility inherent in the human experience.

1.DIGITAL COMFORT

The only laws: Be radiant. Be heavy. Be green.

Tonight, the dead light up your mind like an image of your mind on a scientist’s screen. ‘The scientists don’t know – and too much.’

“In the town square, in the heart of night (a delicacy like the heart of an artichoke), a man dances cheek-to-cheek with the infinite blue.”

(Schwartz, 2022)

a. comfort care

Let’s care for this digital body. I’ll feed it virtual vegetables while you wipe away the wear of battery fatigue. And why not encourage it to take strolls through the network, it might be good for it.

But what if it falls ill? What if its sickness is inherent, designed to echo like the distorted reflection of rippling water a corrupted, isolated, and repulsive physical form? Then we must comfort care for it.

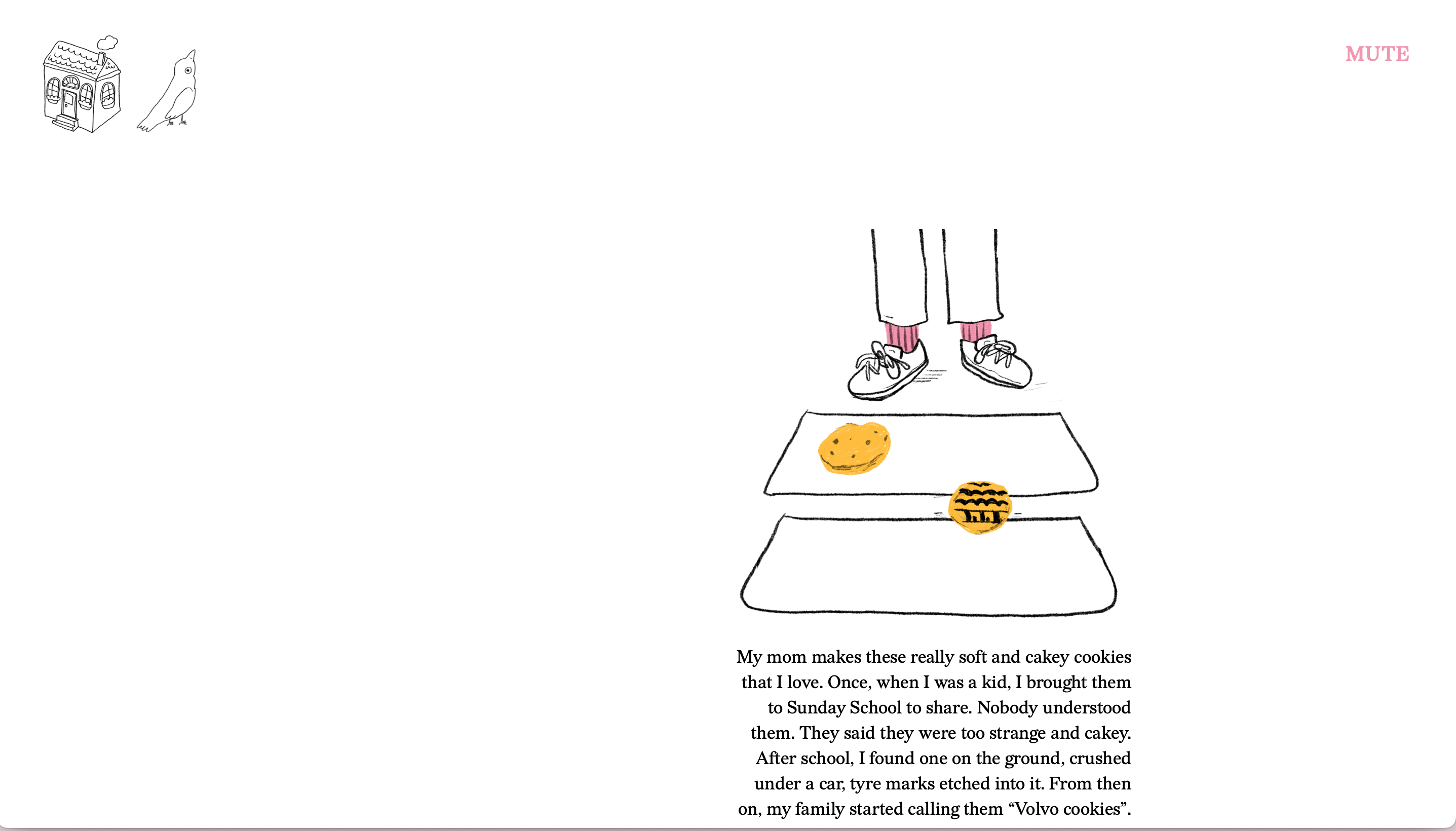

Comfort care is a key concept in healthcare, described as an art. It is the simple but not easy art of performing comforting actions by a nurse for a patient (Kolcaba, 1995). The nurse is in this story an artist full of intention, using the medium of comforting actions to produce the artwork of comfort for the uncomfortable. Subtle, subjective, and thorough. However, achieving comfort for another is far from straightforward. It demands addressing not only the physical but also the psychospiritual, environmental, and socio-cultural dimensions of distress, each requiring its blend of relief, ease, and transcendence (Kolcaba, 1995).

In moments of need, digital comfort may become the only care certain digressive bodies receive. When the distress a body is in becomes too culturally uncomfortable, no nurse will come to check on it.

If care is offered, it’s often only with a desire to assimilate the divergent body back into expected standards of normalcy and ability. This leaves those with non-conforming bodies isolated, ashamed, and yearning for connection and acceptance.I am talking here about the distress caused by mental health issues that have direct connections to physicality—self- injuring in any direct form; food, drugs, pain. The culturally uncomfortable diseases, the it’s- personal- responsibility, and just-stop disorders. This is a hidden topic of this text because I cared more about the pain surrounding them and the reasons to hide rather than the grim physicality of them all.

In the depths of isolation and confusion, marginalized bodies often look for belonging and understanding online. Gravitating towards one another with a hunger born of desperation, forming intimate bonds through shared pain. Through a shared sense of unwillingness, a lack of desire, and a desperate need for physical assimilation with the norm.

The healthy body, the normal body, the loved body.

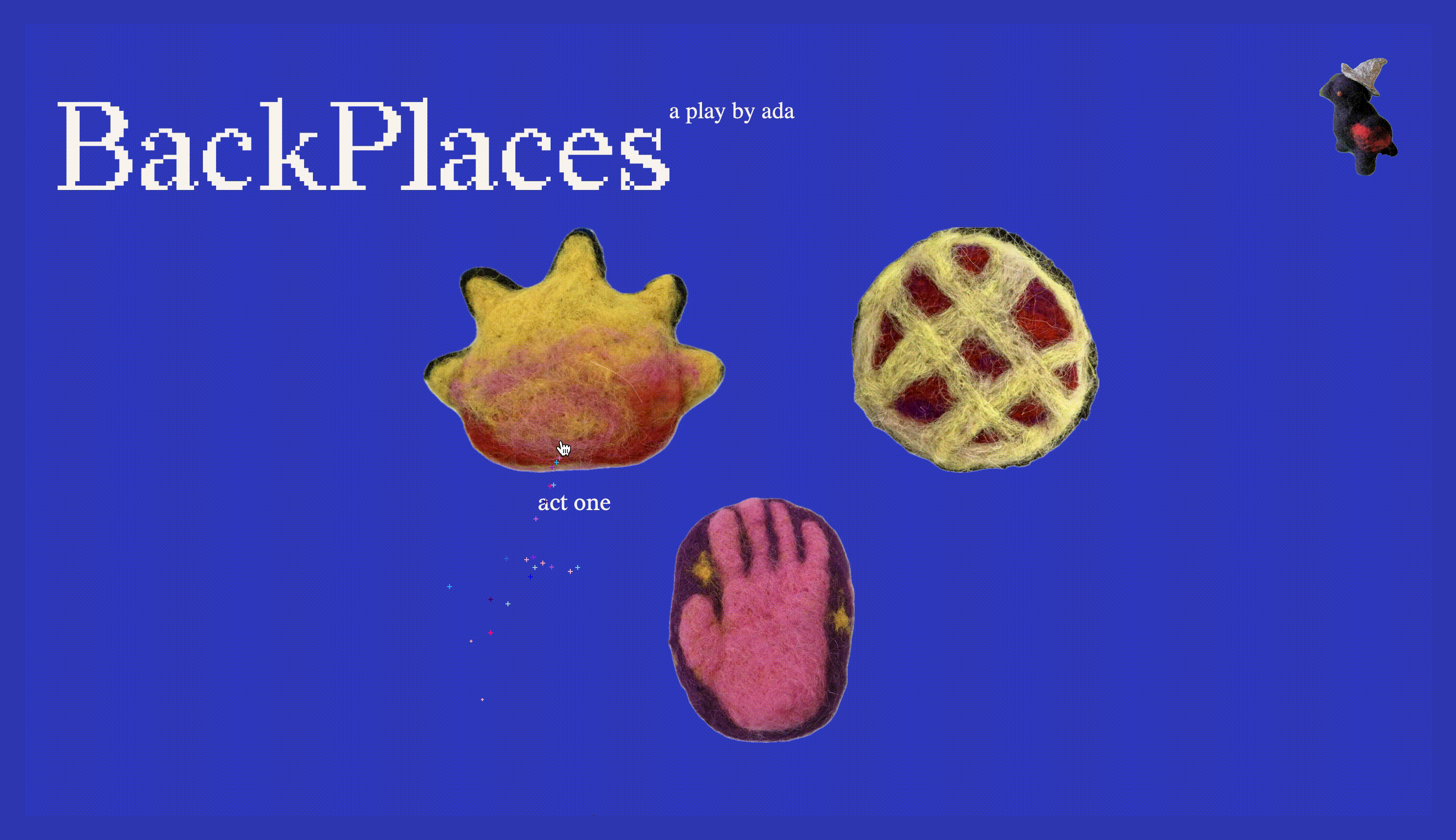

On the internet, these digital bodies claw onto each other, holding each other close and comfort-caring for one another. The spaces where this happens are rooms, or corners of the internet that I’ll call back places. Back places were initially defined by the sociologist Goffman as symbolic spaces where stigmatized people did not need to hide their stigma(1963). In our story, backplaces are small rooms online, tender soft spaces reserved by those in terrible psychological pain themselves, where they can find relief, ease, and transcendence.

Of course, when we speak of digital bodies, their physicality is not relevant. To comfort care for a digital body one would thus need to provide relief, ease, and transcendence for the mental, emotional, and spiritual; through the digital environment of the body and the interpersonal cultural relations of the individual. As with any place of healing, however, it is a transient place. It is an achy place, for the last step of the journey will see them leave the community and compassion that saw and sustained them.

There is no other way for divergent people.

b. uncomfortable comfort

In the past and the present, social scientists have studied the people in the corners of the internet, characterizing these spaces between people as deviant. Like children lifting stones to look at the bugs underneath— simultaneously repulsed and fascinated by the coherence discovered where once was separation. A partition that was then reinforced by the scientists themselves as they began documenting the bugs’ behavior. They eavesdropped on conversations, captured intimate moments, and asked again and again what made them so different. The more they probed, the more they made sure to separate their behavior from the norm to place the deviants against (Adler and Adler, 2005, 2008; Smith, Wickes & Underwood, 2013).

The concept of deviance, particularly concerning what people do with their bodies and how their bodies behave, I find inherently flawed. Observing from an artificial external standpoint only serves to further alienate those already marginalized. I like to approach my research into the intimacy and comfort care expressed in marginalized digital communities without the alienation of social science. There are many approaches one can take if one wishes to avoid this, and the one I am choosing to borrow is a mathematical approach to anthropology. I would like to borrow from mathematician Jörn Dunkel’s work in pattern formation. It’s a conscious choice to approach divergences in bodily behavior through their similarities, not differences. This includes specificities in atypicality, of course, but also the distinctions between me as the writer and them as the writer. You as the reader and you as the community. Me and you, as a whole. Both exist, both separate but in what is not of such importance.

“Though many of these systems are different, fundamentally, we can see similarities in the structure of their data. It’s very easy to find differences. What’s more interesting is to find out what’s similar.”

(Chu & Dunkel, 2021)

Individuals who forge and inhabit these communities, fostering tender, intimate connections amongst themselves, are not deviant but rather divergent. Deviance involves bifurcation, a split estuary from the river of appropriate cultural behavior.Of course, the river itself is not a river; it’s many confused streams that believe themselves both the same and separate. I don’t know where I’m going with this, I just don’t love the river of normativity and I’d rather go swim in the ocean of dreams with you.

Divergence can be so much more than that. In mathematics, a divergent series extends infinitely without converging to a finite limit. A repetition of partial sums with no clear ending, never reaching zero. Mathematician Niels Abel once said that “divergent series are in general something fatal and it is a shame to base any proof on them. [..] The most essential part of mathematics has no foundation”(1826). Drawing a parallel to social relations would then imply that there is no end to divergence, too many paradoxes in the foundation of normativeness to base anything on it.

Harmonic series are, on the other hand, also divergent series. They are infinite series formed by the summation of all positive unit fractions, named after music harmonics. The wavelengths of a vibrating string are a harmonic series. These series also find application in architecture, establishing harmonious relationships. Despite their integral role in human aesthetics, all harmonic series diverge, perpetually expanding without ever concluding. They embody a richness that transcends conventional boundaries, blending into one another infinitely.

By likening digital bodies to divergent series, we embrace the complexity and infinite possibilities arising from their interconnectedness and deviation from the norm. However, it’s crucial to note that the divergence I’m discussing here carries a halo of pain, accompanied by the requirement of bodily discomfort. There are other forms of divergence, ways to have different bodies that necessitate creating spaciousness around normativity to allow them grace to grow.

The divergent digital bodies we are dancing with and caring for, however, are of a particular type. If we were to go back to our water stories, we’d see that the digital bodies we are following are painful ones. Cold, deep streams, hard to follow, hard to swim in. Their divergence from the norm makes them so.

They have intricate relationships with themselves, existing in unstainable forms devoid of comfort, nourishment, or thriving. What does comfort mean for a body whose whole existence is uncomfortable? Moreover, what if the comfort care performed for these divergent bodies makes them too comfortable being in their pained state of self? Could they be?I heard the idea of living questions for the first time in “Letters to A Young Poet” by Rainer Maria Rilke and then again on the podcast On Being with Krista Tippet. It may be a bit transparent but this entire text is informed by the concept of keeping the unsolved in your heart and learning to love it. Not searching for the answers for we cannot live them yet. The point is to live it all. It could be that at some point we will live our way to an answer but it is feeling the questions alive within us that is important. Do you?

Caring for a digital body involves providing it with space to live, giving its experimental bot-feelings tender attention, and revealing your own vulnerable digital body in response. It’s about giving it an audience, hands to hold, eyes that meet theirs in understanding. A rehearsal room, a pillow, a mirror. These rooms, backplaces scattered across the internet, are hidden enough to allow the divergent to comfort- care for one another, sometimes to the point where it is only the same type of divergent digital bodies reflecting back at each other.

So far I have talked fondly of divergence and the harmony of divergent series, and the need to have no finite ending. I’d like to tell you a different story now. Divergent digital bodies are, by this point in our text, built and alive as they can be. They are many, they are together and seeing each other, producing harmonic waves. They are in backplaces on the internet, but they are less safe than they seem. They are themselves resonant echo chambers, with an ongoing risk of catastrophic acoustic resonance.

Acoustic resonance is what happens when an acoustic system amplifies sound waves whose frequency matches one of its natural frequencies of vibration. The instrument of amplification is important for the harmonic series, for the music must not match exactly. An exact match will break it for the object seeks out its resonance. Resonating at the precise resonant frequency of a glass will shatter it. Digital bodies meet in these rooms, amplifying their own waves seeking resonance but the risk of an exact match is that it may shatter them. These spaces full of divergent digital bodies quickly grow unstable, tethering echo chambers. Rooms full of reflections, transforming what was once individual pain into a mirrored loop of anguish. Caring for your own and others’ bodies becomes increasingly difficult, making permanent residence in the mirror room unbearable. You all know you must leave before you meet your exact resonance.

c. unbearable intimacy

This is the end of the story. Our digital bodies have a shape, a sense of life and death, and someone to care for us and to care for. We are alive and have found intimacy with each other.

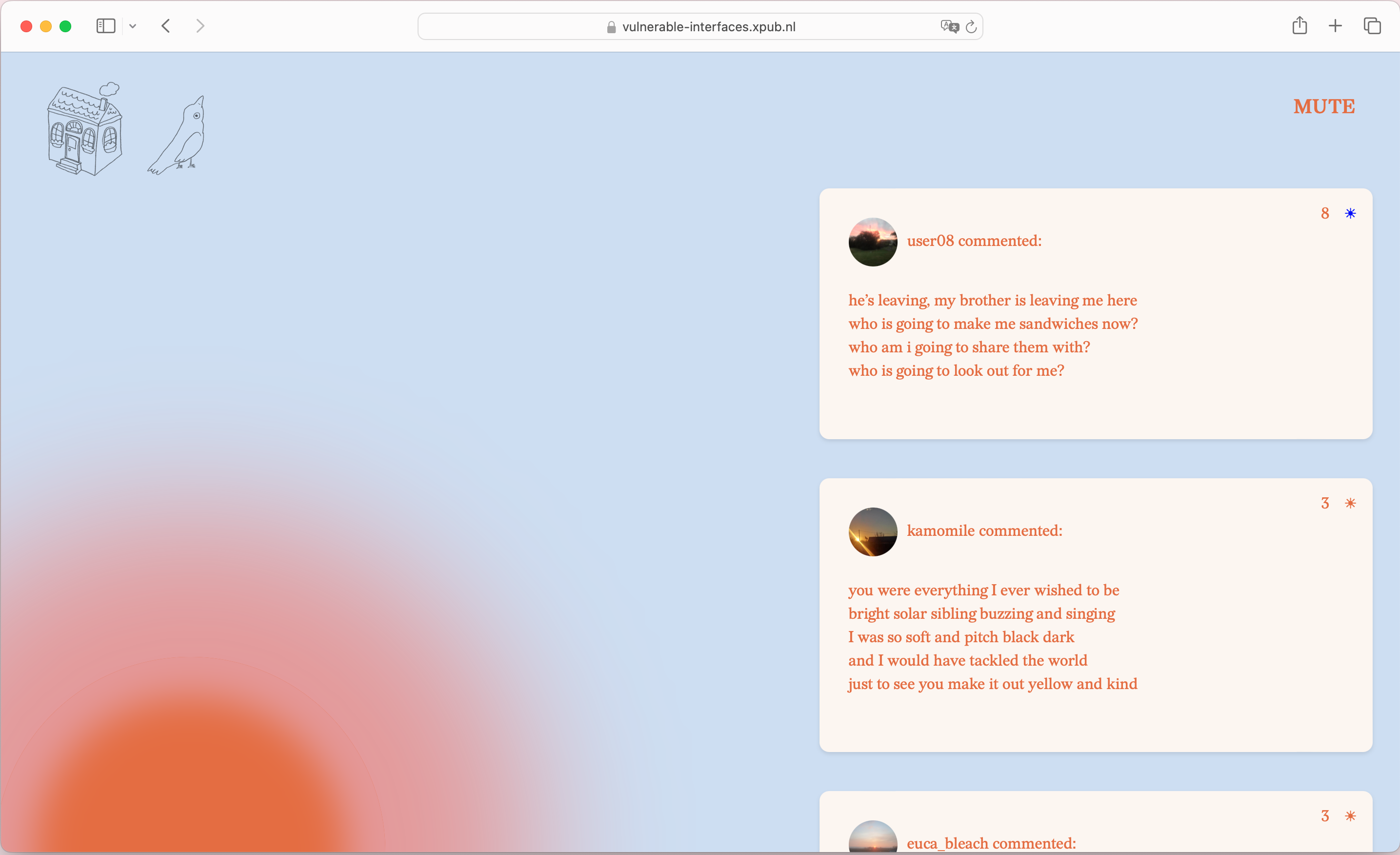

We live in the backplaces, hiding and being hidden online as we have been for years. We used to be on invitation-only forums, password-protected bulletin boards, or encrypted hashtags. Now we are alive in the glitches between pixels, in a shared language of numbers and acronyms and misdirection. Avoiding a content moderation algorithm, always hunting the dashboards of social media websites for visible pain it can cure by erasure. We cannot tell you where to find you or it might too. We try to stay alive, to hold each other, hiding behind code words, fake names, and photos. We care for each other as best we can, the blind leading the blind, the sick caring for the sick. We have brought our unseemliness, our gory gross bodies to each other and found tender intimacy and understanding.

On good days, dashboards are full of goodbyes and my heart swells with hope, for those of us who make it and for the small bright light telling us that we may be one of them. At the same time, some of us leave only to come back ghosts of ourselves, hunting threads with the empty hope of missionaries.

Don’t give up, it’s worth it!

Most of us scoff at this. The idea of leaving only to come back and tell people you left is uncomfortable, the failed progress that washes away hope. A healed patient who regularly comes back to the hospital to encourage the sick, who wish to be anywhere but there. The genuine love and care within these communities transpire better under goodbye posts. When people do heal and shed their accounts’ skin, they often leave it surrounded by all those who once cared for the digital body within it.

I’m so proud of you! Never come back, we love you so much.

Recover, don’t come back. Recover, don’t come back. Recover, never come back.

I had a conversation with a friend who once lived in these spaces between letters but has since moved outside them. When asked, he mentioned he could only find recovery by leaving that community. His body has changed since now it is the spitting image of a standard, healthy body. I didn’t ask, but he knew I’d wonder. He told me he didn’t like his new body and preferred the divergent one he once built himself. Why leave then? Why did you stop?

Because that was no life.

Now life sparkles, everything feels brighter and more exciting. I got my will to live back. Before, there was nothing but my body. I was willing to die for it.

He pulls up the sleeve of his shirt to show me his shoulder, where he has tattooed a symbol for a community friend who died.

I hope I never go back. I miss them every day.

This is the last dichotomy. For the divergent digital body can’t stay in a Backplace for very long, the intimacy of it is unbearable. It is an intimacy that floods, and overruns. In their definition of intimacy in the context of a public surrounding a cultural phenomenon, the author Lauren Berlant denotes that intimacy itself always requires hopeful imagination. It requires belief in the existence of an ideal other who is emotionally attuned to one’s own experiences and fantasies, conditioned by the same longings and with willing reciprocity (2008).If we were to be honest, the entire exercise of writing this for you requires this very faith.

In the context of the intimacy of a Backplace, where divergent digital bodies have formed a community around existing outside the healthy and standard, longing and hopeful intimacy becomes a heavy- hearted and cardinal concept. Being in these rooms and finding care and love for others like you can be so uncomfortable when the longings, experiences, and fantasies you are sharing are centered around pain. The shared cultural experience of existing as a collective divergent digital body promises a fantasy of belonging, a collective hope, and commitment that is extremely fragile.

There is a duality then, if not a dichotomy. As a divergent body, there is nothing you crave more than to be seen and to be loved in a space where you are safe, where the faces looking at you are not repulsed but warm with familiarity. Yet, it is this very warmth that becomes unbearable and an inherently traumatic intimacy. Being loved at your worst, at your most embarrassing, cultural borderline self is an agonizing duality to deal with. McGlotten, who was referenced earlier concerning the potential of bot-feelings of a digital body, now comes back to remind us of their impossibility. In his book, he talks of a digital intimacy that inundates us and is both a source of connection and disconnection (McGlotten, 2013). We are looking at a smaller scale than he does, but intimacy in the context of shared vulnerability can be a need just as intolerable.

Certain kinds of witnessing can become curses, shivers of resonance so close to an explosion of glass if only you strike the cord that will keep me going. Certain kinds of divergence can only end with leaving or death, truth be told. People in these bodies know this, even if the digital bodies behave as if there is hope in a future where the divergence brings joy to one’s life consistently. The shared vulnerability itself then, is unbearable. I need you to see me, I need you, who are just like me at my worst, to love me. When you do, I can’t stand it. It ruins both of us to be seen this way and we need it so desperately. It has to exist and yet it can’t for long.

I leave even though I love all of your digital bodies. I leave because I love you, little digital body and you are me.

2. A LIFE TO BE HAD11

11 Was this the end of this story?

In the epilogue, you sit your body down and enter your computer. The air

coming in from the window smells wet and earthy, new. The sun shines low

on the horizon.

You log in to the internet and realize you are being told a story.

You start to listen, carefully and, full of love, touch the story to let

it know you are there. Delicate-fingered, curious like a child holding a

fallen bird. I hold you and the story tentatively.

I don’t know if I am touching you, to tell you the truth. Digital

bodies are stories, like physical bodies are, like dreams are, and like

water is.

Stories that are hard to tell and hard to hear and even more, maybe,

hard to understand. I have loved these stories and I have loved telling

them to you. I hope you understand that my goal was for you to live

these questions, to feel these stories in their confusion. My digital

body, my bot-feelings, my divergent communities. I have given them to

you, so they may live longer, like an obsolete but beloved cyborg shown

in a museum.

Look: I was here, Look: I was loved, Look: I was saved.

The digital bodies that kept me alive, kept me from becoming fully a

machine are no longer around in these online rooms. They are in

different places, being touched by tentative hands, being loved for more

than their divergence.

I am too.

The rooms, the backplaces, however, are still full of others,

divergent digital bodies who did not leave, who keep caring for each

other at the bottom of the whirlpool. There is no happy ending because

there is no ending. They keep typing and hoping, writing their

collective pain down on keyboards that transmit love letters to each

other. I am not embarrassed by my care for you, but you may be so if it

helps. I know how overwhelming intimacy can be.

Telling you these stories was important for me, so much so that I

will tell you so many more in a different place if you wish to listen to

me longer. With this story, I dreamt of a digital body for you. It came

from an ocean of dreams, into a primordial soup that gave it enough

shape to become wild rivers, deep streams, sound waves. It flooded and

now, it leaves. A digital body that grew its own feelings, looked for

others like it, and realized its divergence and the need to leave. A

dream body, a primordial body, a disruptive body, a divergent body, and

now, a leaving body. This last story, however, of the leaving and loving

body, is yet to be told.

The sun is now almost up, and the birds are alive and awake, telling

each other stories just outside the room. We don’t have so much time

left. I have made you something, to tell your digital body the stories

of the leaving and loving body. It is a webpage, the address is

https://vulnerable-interfaces.xpub.nl/backplaces/.

You open the page, and you are asked to write the characters you see

in a captcha.

E5qr7.

eSq9p.

8oc8y.

Fuck.

You try not to panic, but you know you have been detected.

THANK YOU

Special thanks to Marloes de Valk, Michael Murtaugh, Manetta Berends,

Joseph Knierzinger and Leslie Robbins.

Extra thank you to Chae and Kamo from XPUB3 for the food and moral

support in this trying time and to my other xpubini for being great and

eating my snacks and gossiping.

But most of all I’d like to thank the people in the online communities

I’ve met and loved, you were of course who this thesis was about. Thank

you for saving me, I will always remember you.

references

Adler, P.A. and Adler, P. (2008) ‘The Cyber Worlds of self-injurers: Deviant communities, relationships, and selves’, Symbolic Interaction, 31(1), pp. 33–56. doi:10.1525/si.2008.31.1.33.

Berlant, L.G. (2008) The female complaint the unfinished business of sentimentality in American culture. Durham: Duke University Press.

Chu, J. (2021) Looking for similarities across Complex Systems, MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available at: https://news.mit.edu/2021/jorn-dunkel-complex- systems-0627 (Accessed: 08 March 2024).

Deleuze, G., Boyman, A. and Rajchman, J. (2001) Pure immanence: Essays on a life. New York: Zone Books.

Goffman, E. (2022) Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. London: Penguin Classics. Hafner, K. (1997) The epic saga of the well, Wired. Available at: https://www.wired.com/1997/05/ff-well/ (Accessed: 01 February 2024).

Haraway, D.J. (2000) ‘A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century’, Posthumanism, pp. 69–84. doi:10.1007/978- 1-137-05194-3_10.

Hyacint (2017) Harmonic series to 32,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

Harmonic_series_to_32.svg.

Kolcaba, K.Y. and Kolcaba, R.J. (1991) ‘An analysis of the concept of comfort’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 16(11), pp. 1301–1310. doi:10.1111/j.1365- 2648.1991.tb01558.x.

Leonard, A. (no date) All Too Real, https://people.well.com/. Available at: https://people.well.com/user/cynsa/tom/tom14.html (Accessed: 01 April 2024).

McGlotten, S. (2013) Virtual intimacies: Media, affect, and queer sociality [Preprint]. doi:10.1353 book27643.

Rumi, J. al-Din and Barks, C. (1995) ‘Story Water’, in The Essential Rumi. New

Schwartz, C. (2022) Lecture on Loneliness, Granta. Available at: https://granta.com/lecture-on-loneliness/ (Accessed: 08 March 2024).

Smith, N., Wickes, R. and Underwood, M. (2013) ‘Managing a marginalised identity in pro-anorexia and fat acceptance cybercommunities’, Journal of Sociology, 51(4), pp. 950–967. doi:10.1177/1440783313486220.

Yun, J. (2020) ‘The Leaving Season’, in Some Are Always Hungry. University of Nebraska Press.

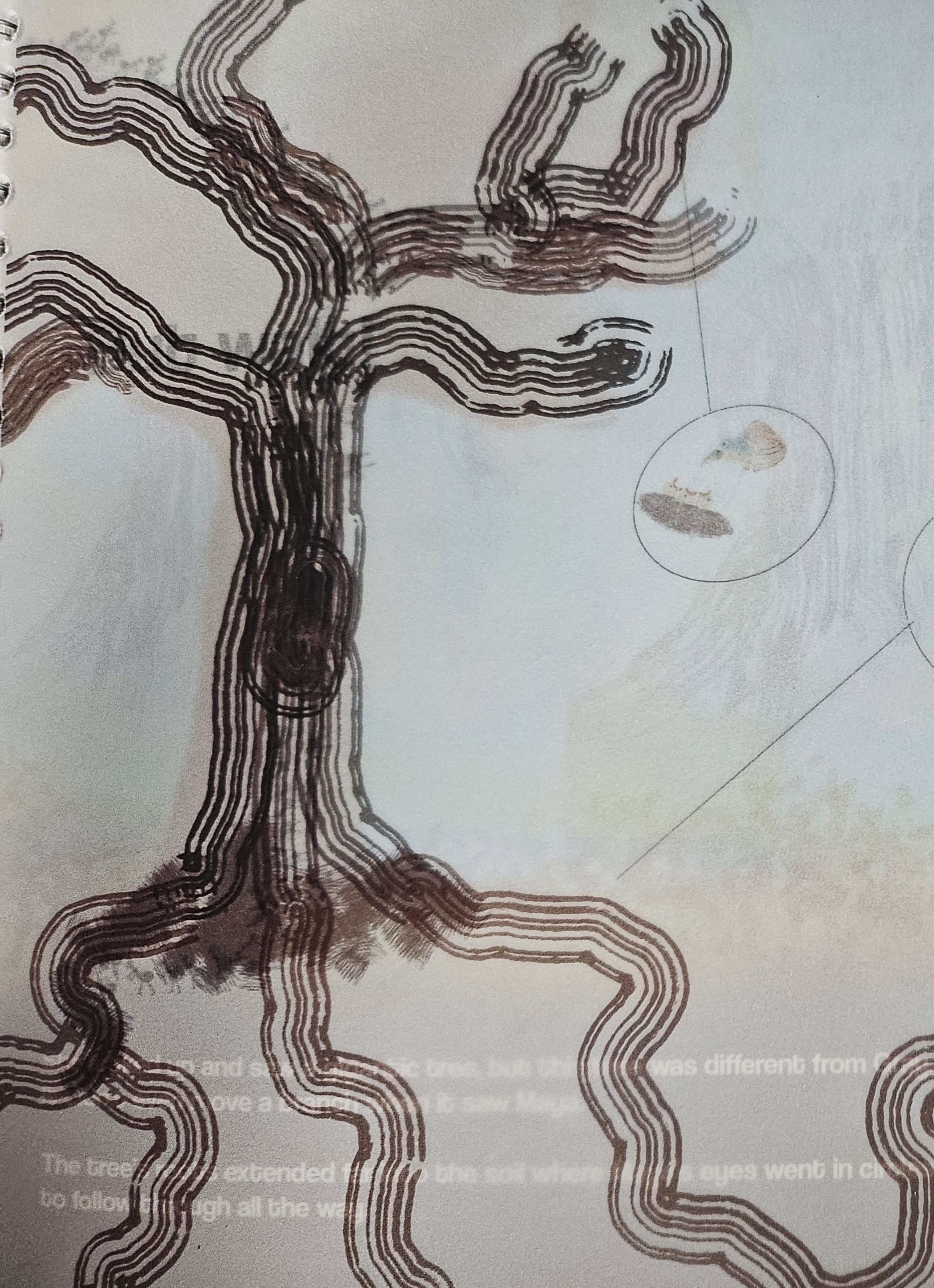

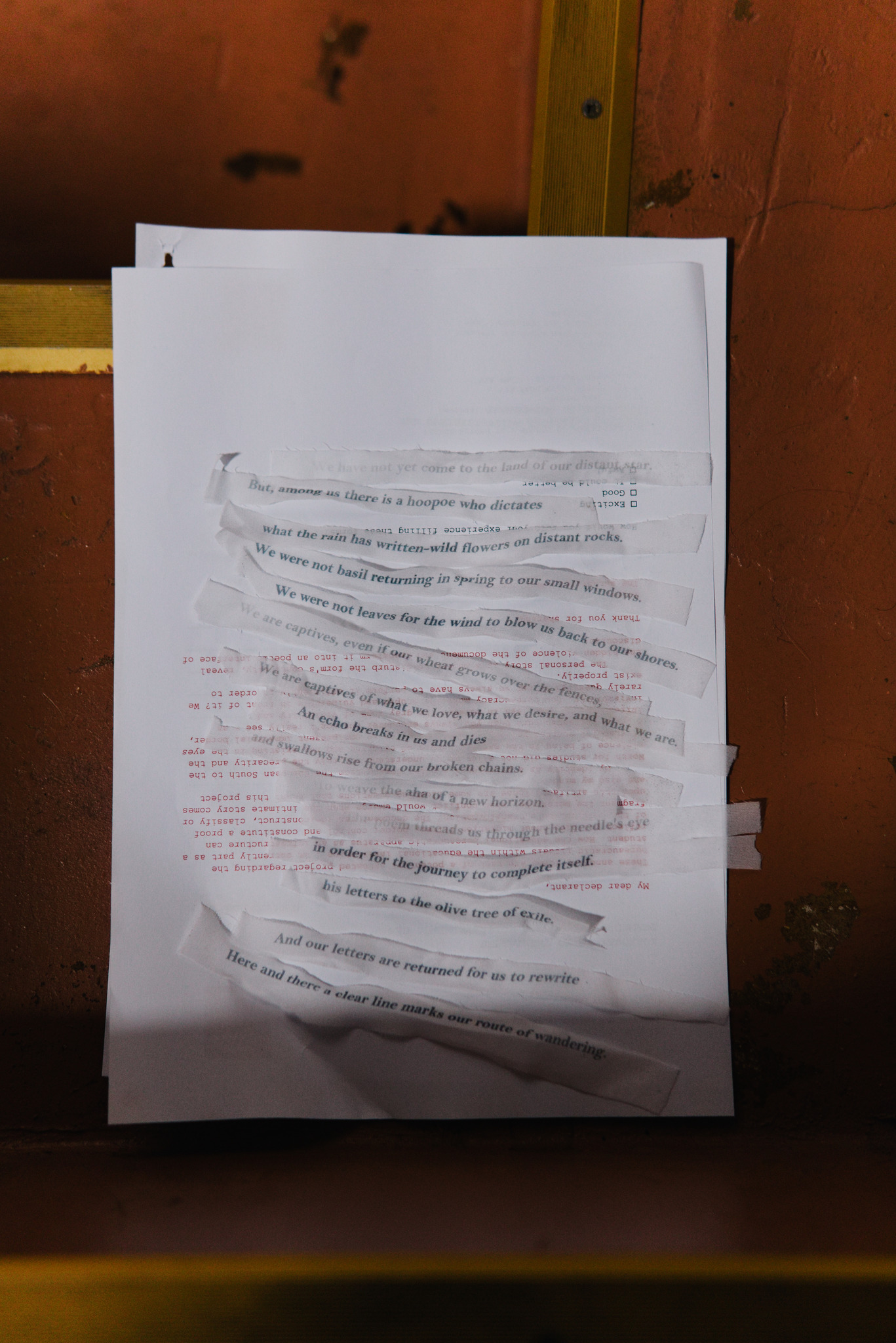

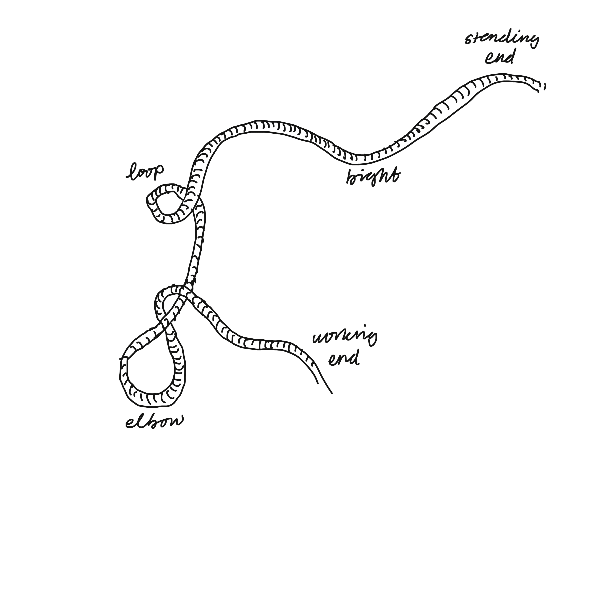

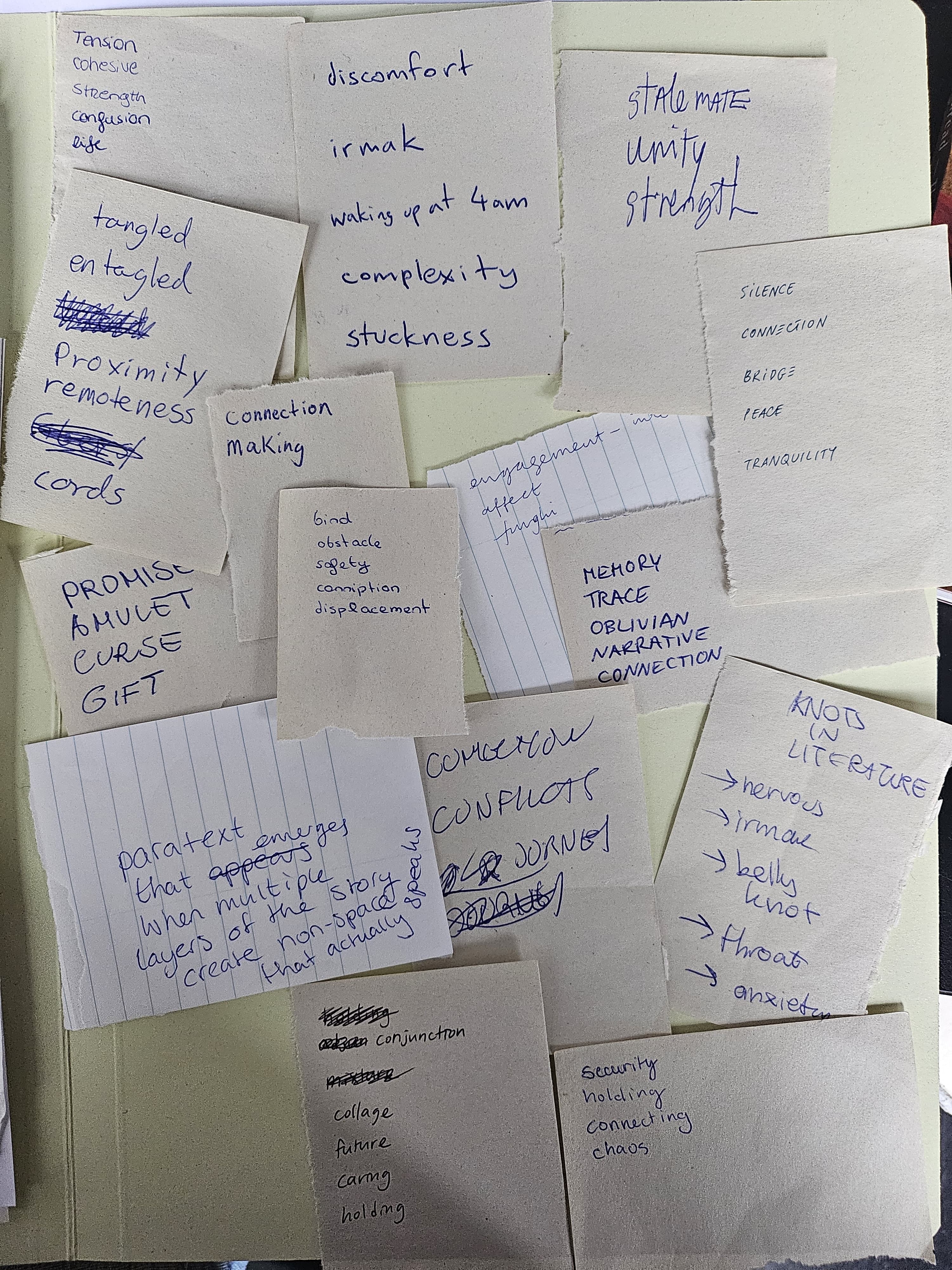

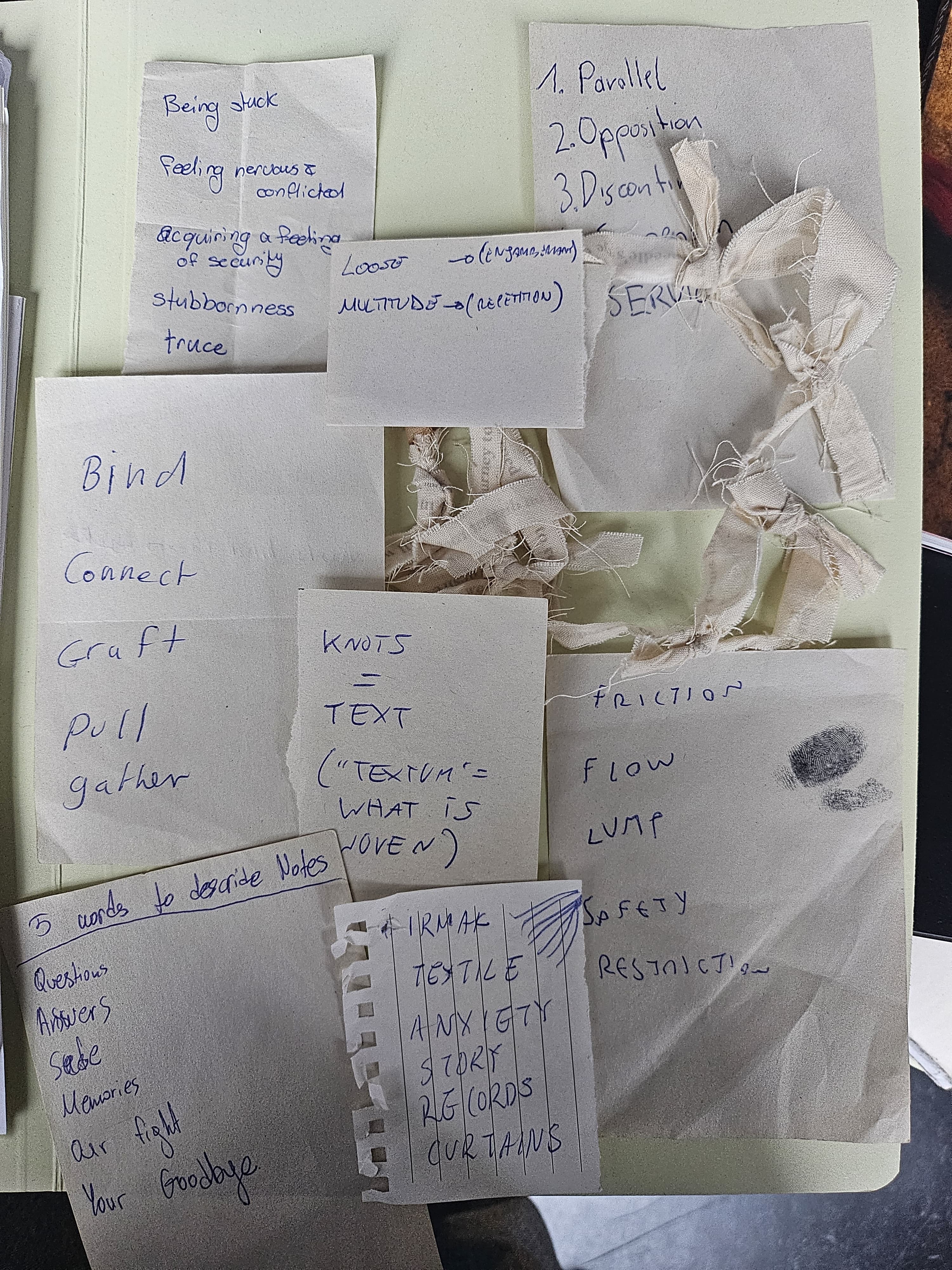

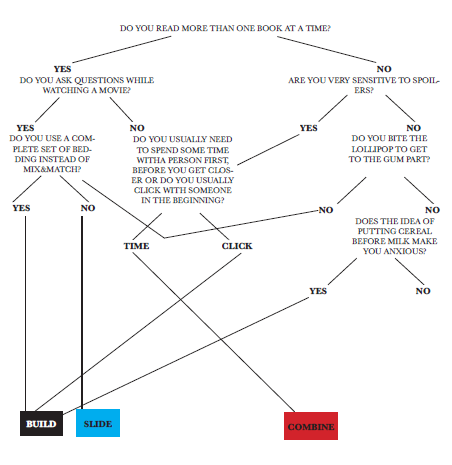

Through

this bight of the thesis, I feel the necessity to clarify my intention

of using knots as a “thinking and writing object” throughout my research

journey. Although knots are physical objects and technically crucial in

many fields of labor and life, they are also objects of thought and are

open for wide minds’ appreciation. Throughout history, knots have been

used to connect, stop, secure, bind, protect, decorate, record data,

punish, contain, fly and many other purposes. So if the invention of

flying -which required a wing that was supported using certain types of

knots was initiated with the knowledge of how to use strings to make

things, why wouldn’t a research paper make use of this wonderful art as

an inspiration for writing and interactive reading?

Through

this bight of the thesis, I feel the necessity to clarify my intention

of using knots as a “thinking and writing object” throughout my research

journey. Although knots are physical objects and technically crucial in

many fields of labor and life, they are also objects of thought and are

open for wide minds’ appreciation. Throughout history, knots have been

used to connect, stop, secure, bind, protect, decorate, record data,

punish, contain, fly and many other purposes. So if the invention of

flying -which required a wing that was supported using certain types of

knots was initiated with the knowledge of how to use strings to make

things, why wouldn’t a research paper make use of this wonderful art as

an inspiration for writing and interactive reading?

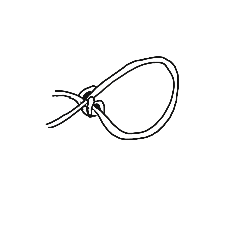

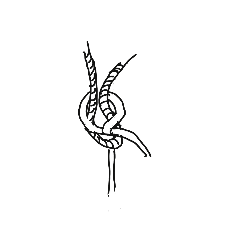

Slipknot is widely

used for catching small animals like rabbits and snares. It is also

commonly used to tie packages.

Slipknot is widely

used for catching small animals like rabbits and snares. It is also

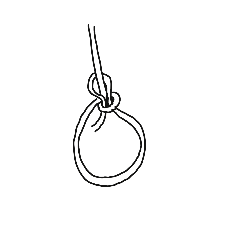

commonly used to tie packages. Bowline is known to

be used since 1627. Some believe it was used in Ancient Egypt because a

knot resembling it was discovered in the tomb of pharaoh Cheops. Even

after it’s used and very tight, bowline is still easy to untie, which

makes it commonly used.

Bowline is known to

be used since 1627. Some believe it was used in Ancient Egypt because a

knot resembling it was discovered in the tomb of pharaoh Cheops. Even

after it’s used and very tight, bowline is still easy to untie, which

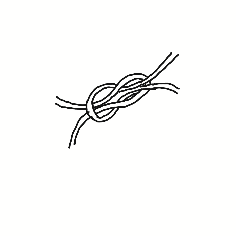

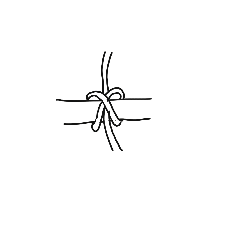

makes it commonly used. Square knot is one of

the oldest knots. Romans knew it as Hercules knot. A roman scholar

claimed that it speeds up healing when used to secure a bandage. It is

often used to tie belts and shoe laces.

Square knot is one of

the oldest knots. Romans knew it as Hercules knot. A roman scholar

claimed that it speeds up healing when used to secure a bandage. It is

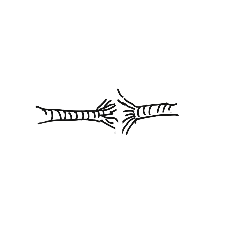

often used to tie belts and shoe laces. Broken

knots are knots that aren’t tied well, done with a wrong material or was

under more pressure than it could take.

Broken

knots are knots that aren’t tied well, done with a wrong material or was

under more pressure than it could take. Bends are joining

knots. They attach two strings together. The bend above is a sheet bend

and it works well when koining two different strings and can take

stress.

Bends are joining

knots. They attach two strings together. The bend above is a sheet bend

and it works well when koining two different strings and can take

stress. Hitches are used to

tie strings to a standing solid object.

Hitches are used to

tie strings to a standing solid object.

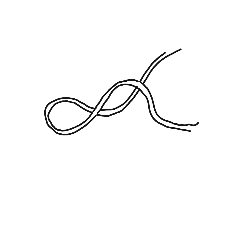

This is the elbow of

our strings. Elbows are created when an additional twist is added to a

loop. In this case, it represents the counter argument in the

string.

This is the elbow of

our strings. Elbows are created when an additional twist is added to a

loop. In this case, it represents the counter argument in the

string.