In response to the abysmal socio-economic inequities and catastrophic ecological collapse we are witnessing globally, powerful resistance and alternative movements are emerging around the world L A. These are articulating and promoting practices and worldviews relating to achieving human and planetary wellbeing in just and sustainable ways. Some of these are re-affirmations of continuing lifestyles and livelihoods that have lived in relative harmony with the earth for millennia or centuries. Others O are new initiatives emerging from resistance movements against the destructive nature of capitalism, industrialism, patriarchy, statism, and other forms of power concentration.

Though incredibly diverse in their settings and processes, these initiatives display some common features that enable the emergence of a general set of principles and values, forming a broad ideological framework, that may be applicable beyond the specific sites where they are operational. One of these features is the assertion of autonomy; or self-governance; or self-determination. This is most prominently articulated in numerous movements of indigenous peoples around the world L A, culminating globally in the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Zapatista and Kurdish autonomy movements L are also based on the principle of autonomy.

One such a framework that has emerged from grassroots experience in India, with significant global resonance, is eco-swaraj. The term swaraj, simplistically translated as self-rule, stems from ancient Indian notions and practices of people being involved in decision-making in local assemblies A. It became popular and widely articulated during India’s Independence struggle against the British colonial power, but it is important to realize that its use to mean ‘national independence’ is a very limited interpretation. MK Gandhi1 , in fact, in numerous writings including in particular Hind Swaraj, attempted to give it a much deeper and wider meaning. Encompassing individual to community to human autonomy and freedom, integrally linking to the ethics of responsibility towards others O (including the rest of nature), and to the spiritual deepening necessary for ethically just and self-restrained behaviour2.

Autonomy and Self-rule

Equally, though, the notion of eco-swaraj emerges from grassroots praxis P 3. This is illustrated in the following examples from three communities in different parts of India:

1. “Our government is in Mumbai and Delhi, but we are the government in our village” , Mendha-Lekha village, Maharashtra.4

The village of Mendha-Lekha, in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra state, has a population of about five hundred Gond Adivasi people, indigenous people who in India are also called ‘tribals’. About thirty years ago these people were part of a resistance movement against a large dam that would have displaced them and submerged their forests A. This mobilisation also led them to consider forms of organisation that could help deal with other problems and issues. They established their ‘gram sabha’ (village assembly) as the primary organ of decision-making, and after considerable discussion adopted the principle of consensus. They realised that voting and the majoritarianism that comes with it can be detrimental to village unity and the interests of minorities. The villagers do not allow any government agency or politicians M to take decisions on their behalf, nor may a village or tribal chief do so on his/her own. This is part of a ‘tribal self-rule’ campaign underway in some parts of India, though few villages have managed to achieve complete self-rule as it is a process that requires sustained effort, natural leadership, and the ability to resolve disputes – features that are not common. Both in Mendha-Lekha and at several other sites, communities are now also using the recent legislation that recognises their communal rights to govern and use forests, along with constitutional provisions of decentralisation, to assert varying levels of swaraj.

2. “These hills and forests belong to Niyamraja, they are the basis of our survival and livelihoods, we will not allow any company to take them away from us”, Dongria Kondh adivasis (indigenous people), Odisha.

The ancient indigenous adivasi group of Dongria Kondh, was catapulted into national and global limelight when the UK-based transnational corporation (TNC) Vedanta proposed to mine bauxite in the hills where they live. The Dongria Kondh pointed out that these hills were their sacred territory A, and also crucial for their livelihoods and cultural existence. When the state gave its permission for the corporation to begin mining, the Dongria Kondh, supported by civil society groups, took the matter to various levels of government, the courts, and even the shareholders of Vedanta Corporation in London. The Indian Supreme Court ruled that as a culturally important site for the Dongria Kondh, the government required the peoples’ approval. This is a crucial order that established the right of consent (or rejection) to affected communities, somewhat akin to the global indigenous peoples’ demand for ‘free and prior informed consent’ (FPIC) now enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. At village assemblies that were subsequently held, the Dongria Kondh unanimously rejected the mining proposal and have since then stood firm against renewed efforts to convince them otherwise, despite increased armed police presence and intimidation tactics by the state.

3. “Seeds are the core of our identity, our culture, our livelihoods, they are our heritage and no government agency or corporation can control them”, Dalit women of Deccan Development Society, Telangana.

In India’s unique caste system (mostly amongst Hindus), where people are born into a relatively unchanging hierarchical ordering of castes, Dalits are at the bottom of the run, oppressed and exploited in multiple ways. As Dalit women, there is double oppression in a society that is also highly patriarchal. And as small and marginal farmers, they are also economically marginalised. In such a situation, over the last three decades, these women R have thrown off their socially oppressed status by achieving a remarkable revolution in sustainable farming, alternative media, and collective mobilisation. Assisted by some civil society activists, they collectivized several agricultural operations, revived traditional seed diversity, went completely organic L A, created grain banks for the poor to access, linked farmer producers to nearby consumers (through a healthy foods restaurant in a nearby town), fought for land rights for women, took up an influential role in the local Agricultural Science Centre (a government set-up), and in many other ways achieved food sovereignty and security. Thus empowered, they also set up a community radio station and a filmmaking unit, to generate their own media content. As part of several national and global networks, they have also participated in policy forums and civil society exchanges. Where once they were shunned as Dalits, marginalised as women, and poverty-stricken as marginal farmers with few productive assets, they are now assertive, self-confident controllers of their own destiny, advocates for local to global policy change, and path breakers in many other respects.

These and numerous other examples across India, including in urban areas such as the movements for the ‘right to the city’, like participatory budgeting, or area sabha (neighbourhood assembly) empowerment as an urban parallel to gram sabha (village assembly) self-governance, show the potential of eco-swaraj.5 Practices of eco-swaraj (as also others O in the world6) display an approach that respects the limits of the Earth and the rights of other species, while pursuing the core values of social justice and equity T. With its strong democratic H and egalitarian impulse, eco-swaraj seeks to empower every person to be a part of decision-making and requires a holistic vision of human wellbeing - that encompasses physical, material, socio-cultural, intellectual, and spiritual dimensions. Instead of states and corporations, eco-swaraj places collectives and communities at the centre of governance and economy. Eco-swaraj is grounded in real-life initiatives across the Indian subcontinent, encompassing sustainable farming, fisheries and pastoralism, food and water sovereignty, decentralized energy production, direct local governance, community health, alternative learning R and education, community-controlled media and communications, localization of economies, gender and caste justice, rights of differently abled and multiple sexualities, and many others O.

Radical Ecological Democracy

Based on such grassroots experience P and interactions with activist-thinkers and practitioners across India, a conceptual framework called Radical Ecological Democracy H (RED) has emerged in the last few years as a somewhat more systematic or structured reworking of eco-swaraj. While it arose in India, it quickly found resonance in many other parts of the world as part of a process of generating Peoples’ Sustainability Treaties for the Rio+20 Conference.7

Eco-swaraj or RED encompasses the following five interlocking spheres (thematic composites of key elements), which have evolved through a process of bringing together alternative initiatives across India called Vikalp Sangam (Alternatives Confluence), begun in 20148:

Ecological wisdom and resilience: Reviving or strengthening the foundational belief in humanity being part of nature, and the intrinsic right of the rest of nature to thrive in all its diversity and complexity, promoting the conservation and resilience of nature (ecosystems, species, functions, and cycles).

Social well-being and justice: Moving towards lives that are fulfilling and satisfactory physically, socially, culturally, and spiritually; with equity T in socio-economic and political entitlements M, benefits, rights and responsibilities across gender, class, caste, age, ethnicities, ‘able’ities, sexualities, and other current divisions; and an ongoing attempt to balance collective interests and individual freedoms; so that peace and harmony are ensured.

Direct or radical political democracy: Establishing processes of decision-making power at the smallest unit of human settlement (rural or urban), in which every human has the right, capacity and opportunity to take part T. From these basic units outwards growth is envisioned to larger levels of governance that are accountable and answerable to these basic units. Political decision-making M at larger levels is taken by ecoregional or biocultural regional institutions, which respect ecological and cultural linkages and boundaries (and therefore challenge current political boundaries, including those of nation-states). The role of the state eventually becomes minimal and is limited to facilitating the connection of peoples and initiatives across larger landscapes. It carryies out welfare measures only till the time the basic units of direct and ecoregional democracy H are not able to do so.

Economic democracy: Establishing or strenthening processes in which local communities A including producers and consumers – often combined in one word as prosumers – have control over the means of production, distribution, exchange, and markets. Open localization is a key principle, in which the local regional economy provides for all basic needs. Dependence on global trade is minimised, without falling into the trap of xenophobic closure of boundaries to ‘outsiders’ (such as what we see in some parts of Europe that are anti-immigrants). Larger trade and exchange, if and where necessary, is built on – and safeguards – this local self-reliance A. Nature, natural resources and other important elements that feed into the economy, are governed as the commons. Private property is minimized or disappears, non-monetized relations of caring and sharing regain their central importance and indicators are predominantly qualitative, focusing on basic needs and well-being.

Cultural and knowledge plurality: Promoting processes in which diversity is a key principle; knowledge and its generation, use and transmission is part of the public domain or commons; innovation is democratically generated H and there are no ivory towers of ‘expertise’; learning takes place as part of life rather than in specialized institutions; and individual or collective pathways of ethical and spiritual well being and of happiness are available to all.

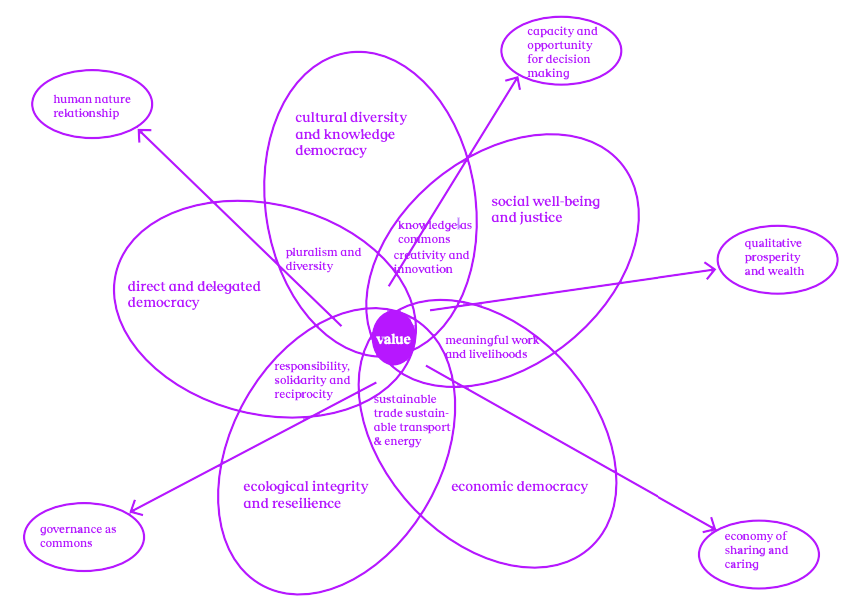

Seen as a set of petals in a flower (see Figure below), the core or bud where they all intersect forms a set of values or principles, which too emerges as a crucial part of alternative initiatives of the kind mentioned above. These values, such as equality and equity T, respect for all life, diversity and pluralism, balancing the collective and the individual, can also be seen as the possible/ideal ethical or spiritual foundation of RED societies, or the worldview(s) that its members hold.

Figure 1 - Spheres of alternative transformation (Note: the topics mentioned in the overlapping areas are only indicative, not exhaustive)

An evolving worldview

The broad components and values of eco-swaraj have been under discussion across India through the Vikalp Sangam (Alternatives Confluence) process. This process brings together a diverse set of actors from communities, civil society, and various professions who are involved in alternative initiatives across all sectors. A series of regional and thematic confluences that began in 2015, enable participants to share experiences, learn from each other, build alliances and collaboration, and jointly envision a better future. Documenting eco-swaraj practices in the form of stories, videos, case studies, and other forms provides a further means of disseminating knowledge, and spreading inspiration for further transformation, through a dedicated website9, a mobile exhibition, and other means.

In 2012, about 20 civil society organizations and movements worldwide L A signed onto a Peoples’ Sustainability Treaty on Radical Ecological Democracy H as part of the parallel people’s process at the Rio+20 Conference in Rio de Janeiro10. Since then, a discussion list has kept alive the dialogue, and opportunities have been found for mutual learning with approaches like de-growth, ecofeminism11, cooperative societies, and social and solidarity economies, buen vivir 12 and its other equivalents in Latin America, and others O. A website launched in September 2017 will also showcase stories and perspectives from around the world13.

RED or eco-swaraj is not a blueprint but an evolving worldview, finding resonance in different forms and different names in different parts of the world. It is also the basis of multiple visions of the future14. In its very process of democratic grassroots P H evolution, it forms an alternative to top-down ideologies and formulations, even as it takes on board the relevant elements of such ideologies. This is the foundation of its transformative potential.

While still struggling in the face of the powerful forces of capitalism, stateism15, patriarchy, and other structures of inequity T and exploitation, alternative approaches like eco-swaraj and RED appear to be gaining ground as more and more people are confronted by multiple crises and searching for ways out. They face multiple challenges from politically M and economically powerful forces whose power they confront; they also find it difficult to mobilise a public that has been seduced by the promise of affluence and the glitter of consumerism, or reduced to seemingnly helpless submission by repressive states and corporations. Nonetheless, they are spreading and finding resonance. Multiple uprisings in various countries and regions on issues such as state repression, corporate impunity, climate crisis, inequality, racial and ethnic conflicts, landgrabbing, dispossession and displacement of communities in the name of ‘development’, are only the more visible signs of this. Quieter, but equally important, are the myriad attempts at finding equitable, sustainable solutions to problems, some examples of which are given above.